Book Reviews

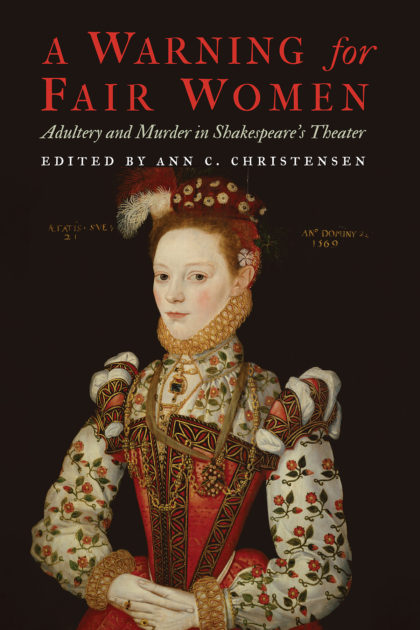

Review of Ann C. Christensen’s A Warning for Faire Women: Adultery and Murder in Shakespeare’s Theater.

Ann C. Christensen’s edition of A Warning for Fair Women (U. of Nebraska Press, 2021) not only offers the early modern dramatic canon a new example of domestic tragedy but proves that the genre of true crime had as much of a hold on audiences then as it does now. A play about the household, relationships, and, most importantly, murder, A Warning for Fair Women dramatizes the captivating characteristics of modern true crime documentaries by staging the details of the 1573 murder of George Sanders. Demonstrating expertise in A Warning for Fair Women as well as in stage conventions, early modern history and law, and the existing canon, Christensen has compiled a beautifully edited and skillfully contextualized play that is useful for any student or scholar of Renaissance Drama.

Ann C. Christensen’s edition of A Warning for Fair Women (U. of Nebraska Press, 2021) not only offers the early modern dramatic canon a new example of domestic tragedy but proves that the genre of true crime had as much of a hold on audiences then as it does now. A play about the household, relationships, and, most importantly, murder, A Warning for Fair Women dramatizes the captivating characteristics of modern true crime documentaries by staging the details of the 1573 murder of George Sanders. Demonstrating expertise in A Warning for Fair Women as well as in stage conventions, early modern history and law, and the existing canon, Christensen has compiled a beautifully edited and skillfully contextualized play that is useful for any student or scholar of Renaissance Drama.

Christensen contends that we “ought not to fault A Warning’s failure to comply with a Shakespeare-based ‘norm,’” but instead use this play to “expand our sense of popular entertainment in the period in order to get at the kind of cultural work this play seems to perform” (xi). This edition of the play follows Christensen’s statement above in that she carefully considers readers familiar with a Shakespearean canon and expands our view of early modern culture through her resources and thorough explanations of the many aspects of this anonymous play. Although this play was performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men and likely, then, fit with the company’s repertoire (xxiv), Christensen convincingly notes that there are non-Shakespearean characteristics of the play that make it a valuable and interesting addition to the canon. As she says, the importance of A Warning comes from its inclusion of generic and stage qualities we do not get in Shakespeare, because he did not write a domestic tragedy, nor did he rely on “dumb shows” or set his plays in contemporary London (xi). Thus, these things that Shakespeare did not do are the very things that Christensen uses to organize her introduction and provide the necessary context for A Warning for Fair Women.

The genre of “domestic tragedy” is well detailed in this edition, which in itself is a valuable addition to the conversation of early modern genres. Christensen identifies the elements which make up domestic tragedy as “nonaristocratic, bourgeois characters, small-scale domestic (or private) settings, and contemporary ‘realistic’ touches” (xx). Such a succinct summary of the domestic tragedy already sets up readers to experience this genre, but Christensen expands on the specifics of A Warning’s approach to domestic tragedy by applying Andrew Gurr’s “documentary drama” – a more “factual” drama that is similar to a history play – to her discussion of genre (xxviii). The blending of genres is nothing new to readers and scholars of early modern drama, as we all recognize the tragicomedy. Christensen’s introduction to this suggests another blend that creates an early modern version of the modern true crime drama: the “realistic” elements of a courtroom scene and a household that blends with the tragic allure of the stage, or as Christensen says, “moments of shock, suspense, and pathos” (xxviii).

Any discussion of genre would be incomplete without a discussion of gender, which Christensen does in such a way that effectively shows the value of this non-canonical play. We are familiar with the kinds of female characters within city comedy as well as tragedy: the feisty young maidens, the vicious ladies, and the stoic victims of masculine abuse. But what about the woman who wants a new lover? Or, more importantly, the woman character based on an actual woman featured in a pamphlet? Christensen’s discussion of gender and genre are based on one of the source materials for A Warning, Arthur Golding’s A briefe discourse of the late Murther of master George Sanders (conveniently included in the back of the edition), and contends that the anonymous playwright “transformed the source material’s outline of events into a grisly—if also often homey—drama that initially follows Anne and George Sanders’s movements through an ordinary day” which influences the character of Anne (ix). Anne stays home while her husband works, and their domestic arrangement contributes to the genre of domestic tragedy and, furthermore, the “brief review of the household makeup in this play illustrates scholars’ expanding definition of early modern domestic life” (xxxiv). Christensen shows that Anne’s character becomes more complicated than a realistic representation of a housewife. Anne Sanders’s character is from a pamphlet about murder: The pamphlet includes “a sinner’s dramatic repentance to reform his readers,” thus, a warning for fair women, which was typical of this type of murder pamphlet (ix). Anne’s character, by the end of the play, brings in another “discursive phenomenon—the mother’s blessing” and Anne “performs a number of exemplary ‘last acts’: she confesses and repents her crimes, accepts her punishment… blesses her children, and says her goodbyes” (xlv). Anne’s role, then, becomes not just a tragic figure, but a warning which refers back to the character’s pamphlet origins. Christensen’s research and presentation of Anne, in this edition, contributes greatly to the conversation of female characters, especially those female characters who are shaped by their genre.

Perhaps the most valuable, interesting, and meaningful aspect of this edition is Christensen’s experience with and passion for A Warning for Fair Women, which shows through in her careful editing and annotating of the play. Seeing the play performed and read aloud has allowed Christensen the necessary exposure to not only know the play, but to understand the intricacies, the humor, the tragedy, and the artistic rendition of a real murder (xi-xii). The play itself, unfamiliar to faithful readers of the Shakespearean canon, benefits greatly from Christensen’s notes and her short summaries before each scene. Her stage directions read as someone who has been a careful theatergoer and reader, and they add to the reading experience in a unique and often very funny way. For instance, in the very first scene, the character of Tragedy not only notices History on the stage, but, according to Christensen, “does a cartoonish double-take” (s.d. 1.27-28). These kinds of details, from someone who has the necessary expertise to provide such details, bring the play to life and show the interesting characteristics and staging potential that can be found in an anonymous play, characteristics that might be overlooked because they are not as “polished” as other early modern plays.

Christensen’s passion for this play also manifests in her detailed and practical guidelines for incorporating A Warning in the classroom through a list of prominent themes. This guide of “topics for discussion, research, and writing assignments” is something that is invaluable to any student, scholar, and teacher of Renaissance drama (liii). The topics include place, space/setting, economic exchanges/economic languages, roles of the church and state, the supernatural and the occult, work and professional identity, masters and servants, public and private, source material, and beauty and virtue. Each of the itemized themes in this section offers something different to expand the reader’s thoughts on the topic and to connect that topic and the play back to prominent works of criticism. For instance, the section titled “Work and professional identity” begins with open questions, aimed at students – “What constitutes work in the play? Who performs work on stage?” – and then outlines some examples of work to consider, such as carpenters who will “kick back for a drink” after work and the Mistresses Drurie and Sanders who are “skilled in ‘physic’” (lv-lvi). This section, like others, ends with suggested reading made up of a few specific works or collections of criticism that can be applied to the play. The care put into this section, appearing at the end of the introduction and right before the play begins, concisely reviews and rearticulates the highlights of the play. Furthermore, this section reads as a perfect review of Christensen’s goal: it contextualizes the play and places it within early modern drama conversations and argues clearly for the value of adding a play like this to the canon.

Venturing outside of the early modern canon is a daunting task for those unprepared. Christensen’s dedication to this anonymous play indeed proves that a lot of work must be done to present this play in context, but it also shows the incredible pay off. An introduction and historical appendix like this allows readers to not only learn about A Warning for Fair Women, but about the early modern period more broadly. Christensen’s approach to law, punishment, gender, and the early modern household through A Warning for Fair Women proves that this is an important addition to the canon of Renaissance drama. The preface to this edition questions how “the current canon [can] limit our access to other works,” and Christensen shows readers that our understanding of the very lifestyle of early modern people can only be enhanced by expanding the canon (xi). With careful and passionate editors like Christensen, the expedition of an unfamiliar play becomes easier and more enjoyable.

A Warning for Faire Women: Adultery and Murder in Shakespeare’s Theater. Christensen, Ann C. University of Nebraska Press, 2021. 320 pp. $99.00. ISBN 978-1-4962-0836-1.