Book Reviews

A Review of Amanda Wrigley and John Wyver’s Screen plays: Theatre plays on British television

People working on “Screen Shakespeare” may overlook this collection of essays exploring the perks and problems of putting all sorts of plays on British television. Shakespeare is not in the title or subtitle of this book and is barely mentioned in the catalog copy. Yet, several of the essays touch on Shakespeare, some in considerable depth, and two explore ten television productions of plays by other early modern playwrights, making this book well worth the attention of scholars working on television plays adapted from Shakespeare and his contemporaries. This review pays scant attention to most of the chapters without Shakespearean content with one exception, explained below, with the result that it seems most effective to consider some chapters out of order.

People working on “Screen Shakespeare” may overlook this collection of essays exploring the perks and problems of putting all sorts of plays on British television. Shakespeare is not in the title or subtitle of this book and is barely mentioned in the catalog copy. Yet, several of the essays touch on Shakespeare, some in considerable depth, and two explore ten television productions of plays by other early modern playwrights, making this book well worth the attention of scholars working on television plays adapted from Shakespeare and his contemporaries. This review pays scant attention to most of the chapters without Shakespearean content with one exception, explained below, with the result that it seems most effective to consider some chapters out of order.

John Wyver’s first chapter on the history of plays on British television creates a context for everything that follows and notes an infinite variety from live broadcasts from theatres, live broadcasts staged in television studios, recorded broadcasts of both, and the ebb and flow of broadcasting or not broadcasting plays, depending on the attitudes of the people in charge at a given time. The broadcasting of plays comes in and out of fashion again, and again, and again. Shakespeare tends to lead the flows and may not be completely absent during the ebbs. This is not a chapter about Shakespeare on television, but because Shakespeare was broadcast so frequently on both the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and Britain’s independent broadcasting services, a dozen Shakespeare broadcasts are referenced, with some discussed in depth.

Chapters 2 and 4 consider broadcasts of plays by the other early modern playwrights. Lisa Ward’s purpose in chapter two is to determine if the BBC Written Archives in Reading is a good place to research early television broadcasts of plays by looking at the records for early modern plays transmitted in 1938—John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, Thomas Dekker’s The Shoemaker’s Holiday, and Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle— but first, bit of background. All three shows went out long before technology was invented for recording live television broadcasts, and the BBC is unlikely to have preserved these broadcasts even if they could have recorded them. One of the frustrations for historians of British television and radio are the purges the Corporation made of old shows to clear storage space once recordings could be made, often recording new shows over old, usually making the Written Archives and contemporary references in the press all that researchers have for thousands of programs. The fullness of Ward’s archival findings depends on the play. The Dekker and Beaumont plays have scant records, but Ward reveals the little there is in a half-page for each. Webster’s play has quite a lot of documentation in the archive, taking eight pages in Ward’s chapter. The set design, camera script, and other materials, plus Ward’s exposition of narrative changes made for this adaptation, give a good sense of how the play was screened. This chapter is fascinating.

So is Susanne Greenhalgh’s fourth chapter on seven broadcasts of two of Middleton’s plays between 1969 and 2009: two productions of Women Beware Woman, one by the BBC and one by Granada; and five of The Changeling, three by the BBC, one by Granada, and a free adaptation called Compulsion broadcast on ITV. After surveying all seven and noting the changes made so producers could address the issues of their time, Greenhalgh concludes, “The presence of Middleton’s plays on British television has been largely due to the enthusiasm of his adapters and producers, several of whom have a theatre background. However, the productions often omitted, diluted or ‘Shakespeareised’ the most grotesque and theatrical elements of his work in favor of more realist televisual styles familiar to a domestic audience. Nevertheless, ways were often found to make the confined space of the television studio mirror and magnify the spatial violence against women at the core of Middleton’s dramaturgy” (106).

Between these is an excellent chapter about producer Basil Dean’s 1938 outside live broadcast (“outside” meaning outside the studio). Cameras were brought into St. Martin’s Theatre in London to screen J. B. Priestley’s When We Were Married during its regularly scheduled performance, though the audience paid half-price to compensate them for the nuisance of the cameras and extra lights. There is a paragraph referencing a 1939 broadcast of Twelfth Night from London’s Phoenix Theatre, but the only thing we learn about the show is that this play was the BBC’s next outside broadcast.[1]

Chapters 5 through 8 are also of limited interest for Shakespeare studies. Chapter 5 is about a series of Harold Pinter plays in 1967, plays that began as radio or television scripts and were remounted for BBC2. Authors Amanda Wrigley and Billy Smart study both public reception and Pinter’s growing reputation. In chapter 6, Les Cooke surveys four broadcasts on local television services of plays performed by the Victoria Theater in Stoke-on Trent. These dramas were set in the region and broadcast to the region. John Wyver returns in chapter 7 with a fascinating 1969-70 experiment by Granada television to create a theatre company to stage plays that could then be adapted for television, the Stables Theatre Company. Wyver explores what he calls “the aspirations and achievements of the Granada project, as well as the reasons for its failure” (150). Ten of the plays staged were broadcast. Romeo and Juliet was produced on the Stable stage and recorded in 1969, but that recording was not considered very good and was held back. Sally Snow’s chapter 8 is about the staging and televising of Black Feet in the Snow, a performance piece by Guyanese poet and playwright James al Ali. The TV version preserved Ali’s radical intent and form. This chapter lays out the reasons for its success.

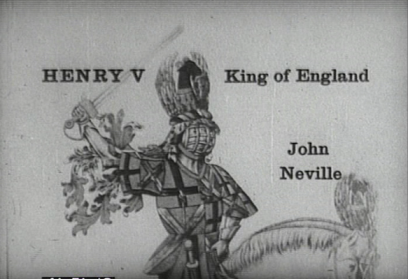

Chapter 9 examines the merits and demerits of Cedric Messina as a producer and sometimes a director of plays for television. Messina had three constants for the shows he produced. The first was to include decorative details in sets and costumes and linger on the beauty of nature when scenes were recorded outdoors. Second was to tell stories as straightforwardly as the medium permits. The third was to employ star actors. Messina believed that the three together would please audiences. These one-size-fits-all practices applied to every play Messina produced, no matter how different those plays sometimes were. Using a case-study approach, Billy Smart examines what achieving these goals meant for Messina’s productions of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (1973), The Merchant of Venice (1972), and J. M. Barrie’s The Little Minister (1975). Smart notes the problems: the visually lavish Pygmalion worked against Messina’s plain style as a director. The Merchant of Venice had a parallel problem: “camera movement concentrates upon the detail of the set rather than nuances of the drama.” The outside broadcast technology for The Little Minister allowed Messina to “open out his production, with the intention of adding extra-textual visual pleasure.” The result was an audience response that was “remarkably consistent” between the three productions, with viewers experiencing “real pleasure” from the “attractive period detail and clear storytelling” (205). This does not mean that the plays were well served. Messina conceived The BBC Television Shakespeare series (U.S. title The Shakespeare Plays) and produced the first two of that show’s seven seasons. Messina tended to hire directors who adhered to his three values, so the weaknesses found in Messina’s style are briefly applied to two plays he produced for The BBC Television Shakespeare with The Little Minister offered as a preview of As You Like It (directed by Basil Coleman, 1978) and Henry VIII (directed by Kevin Billington, 1979) in the first year of BBC Shakespeare series. All three included scenes recorded outdoors or in great houses. The “grandeur of the location” in The Little Minister is shown to work against the “dramatic interest of the scene” in that play (204) which parallels problems with the on-location recordings of the Shakespeare broadcasts.

The book returns to non-Shakespearean drama for the next four chapters. Ruth Adams determines the quality of Abigail’s Party on both stage and screen in chapter 10. I am not sure this is the worthiest chapter in the book in part because I do not think many readers will care about the dramatic qualities of the play or the broadcast at this remove and because Adams tells us little new about televising plays.

We skip to chapter 13 and will return to 11 and 12. Cyrielle Garson examines what are called “verbatim plays,” plays about actual incidents of injustice across society, dramatizations created after interviewing the people involved. Her thesis is that when verbatim theatre is televised, it is “subject to new constraints and pressures imposed by the change of medium, and […] such a process of remediation is politically marked” (263). Garson makes the original plays seem exciting even when the later broadcasts are compromised.

Circling back, chapters 11 and 12 study performances spaces in the televised plays of Samuel Beckett and Henrik Ibsen. Taking these out of order, Stephen Lacey’s twelfth chapter on three television productions of Ibsen notes how well the naturalism of the sets suit the naturalism in the scripts and the performances. Lacey is good on Ibsen, but he studies the performance spaces created for different plays so there is no compare and contrast. Lacey achieved his goals, but Jonathan Bignell achieves more in chapter 11.

Bignell is all about compare and contrast, and that is the genius of his chapter. The author compares the use of space in fourteen television / film adaptations of eleven plays by Beckett, but the soul of his chapter is his comparison of the playing spaces in four broadcasts of Krapp’s Last Tape in 1963, 1971, 1972, and 2007, and include comments about theatrical spaces when a broadcast adapts a stage production. Bignell’s comparisons of the Krapp’s broadcasts explore ways that each set supports, enlarges, or stifles the words of the text, and his comments about all four are enlightening.

As a student of Shakespeare in the media, I found Bignell’s approach thrilling. Television playing spaces are under explored in Shakespeare studies. Beckett’s plays are far different from Shakespeare’s, of course, but Bignell inspires me to think about multiple film and television broadcasts of any Shakespeare play and how the playing spaces might support, enlarge, or stifle those texts. Such engagements are found occasionally for individual productions, and Billy Smart’s observations about Cedric Messina’s The Merchant of Venice fit well here. As Neil Taylor shows in the next chapter, the set in Jane Howell’s BBC Television Shakespeare broadcasts of the first tetralogy in 1983 have been much commented on, but I have never seen comparisons of playing spaces for multiple productions of any Shakespeare’s play. Bignell makes this statement near the end of his chapter, “The study of Beckett’s theatre plays as presented on television offers an exceptional opportunity to analyse how adaptations strategies recur across the decades and are affected by a range of textual and extra-textual forces” (241). While that statement is about Samuel Beckett, it holds much promise for a new approach to Shakespeare screen studies.

Neil Taylor co-edited an important edition of Hamlet with Ann Thompson for the Arden 3 series. He studies the impact (usually the lack of impact) of televised Shakespeare plays on the performance histories in editions of Shakespeare’s works. “Its presence is unevenly distributed across the field, and quite a few editors ignore it entirely” (283). Inclusion grew a little with the broadcast of The BBC Television Shakespeare starting in 1978, but studying television productions remained slim for the most part. When these were discussed, “many of them are described in exactly the same terms that editors employ when describing productions in the theatre” (285). Too often editors criticize television actors for not delivering a speech the way the editor wants to hear it or complain about physical characteristics of the actors. In other words, editors complain that broadcasts fail to be the play in the editor’s head. There is also a problem with descriptions of camera placement and movement: “When editors venture beyond discussion of what a director gains through the power of the close-up, it is usually to reflect on what is lost in the translation of Shakespeare to what they repeatedly call the small screen” (289). There are a couple of exceptions. Many editors praise and write insightfully about Jane Howell’s televised first tetralogy (her televised The Winter’s Tale of 1981 is not mentioned) and about Jonathan Miller’s Timon of Athens, 1981 (also for The BBC Television Shakespeare), but these broadcasts are the most notable exceptions to the general indifference to television in performance histories. Taylor ends with a call for editors to regularly consider television broadcasts of Shakespeare’s plays and to add “a production’s social, political, cultural or historical contexts” (294).

Screen plays: Theatre plays on British television has a lot to offer scholars of screen Shakespeare, television broadcasts by his contemporaries, and the writers of performance histories. Your campus librarian may overlook the book. It was published by Manchester University Press in 2022.

[1] Curious readers may learn more about this performance and broadcast from John Wyver’s blog: https://screenplaystv.wordpress.com/2011/12/11/in-the-beginning-twelfth-night-bbc-1939/