Theater Reviews

The Hollow Crown’s “Richard III”: The Affective Failure of Direct Address

Elizabeth E. Tavares (Pacific University)

The character of Richard III is tricky to manage for contemporary audiences. His villainy is as rich and delicious as that of Milton’s Satan—and therein lies the trap. Portray Richard as a motiveless villain from the start, and all of the play’s dialogue equating his body with his morality rings true: one disfigured on the outside must necessarily be so on the inside. Yet it is this grotesque principle that this final episode of the second series of The Hollow Crown doubles-down on. It has kept me from finishing my reviews for nearly a year, having been so frustrated by the cruel one-dimensionality of ableism on view here that Hollywood is wallowing in at the moment, from Me Before You (2016), The Theory of Everything (2014), I Am Sam (2001), and My Left Foot (1989), to Avatar (2009), Doctor Strange (2016), and the X-Men franchise (2000–2018).

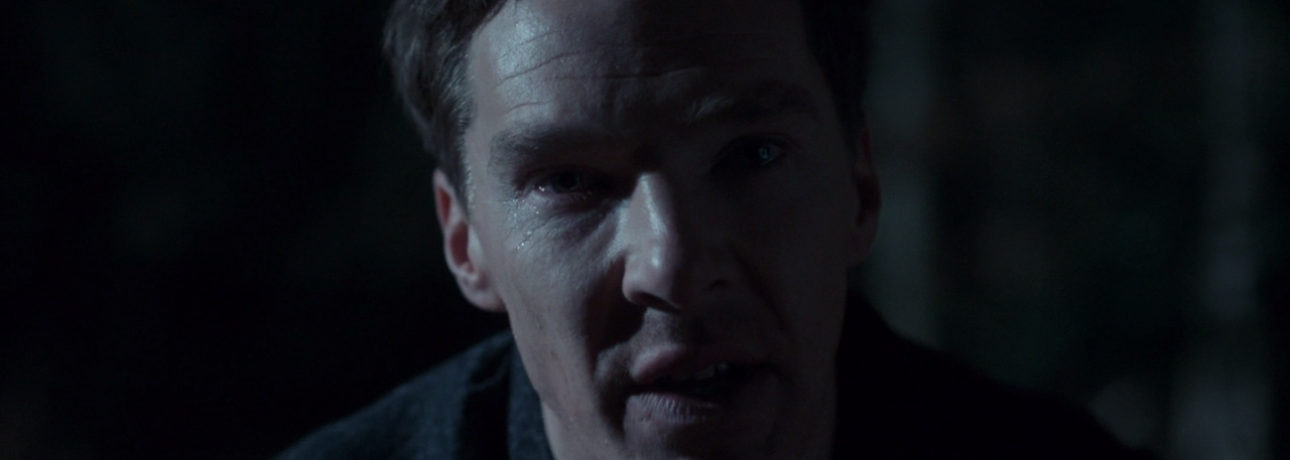

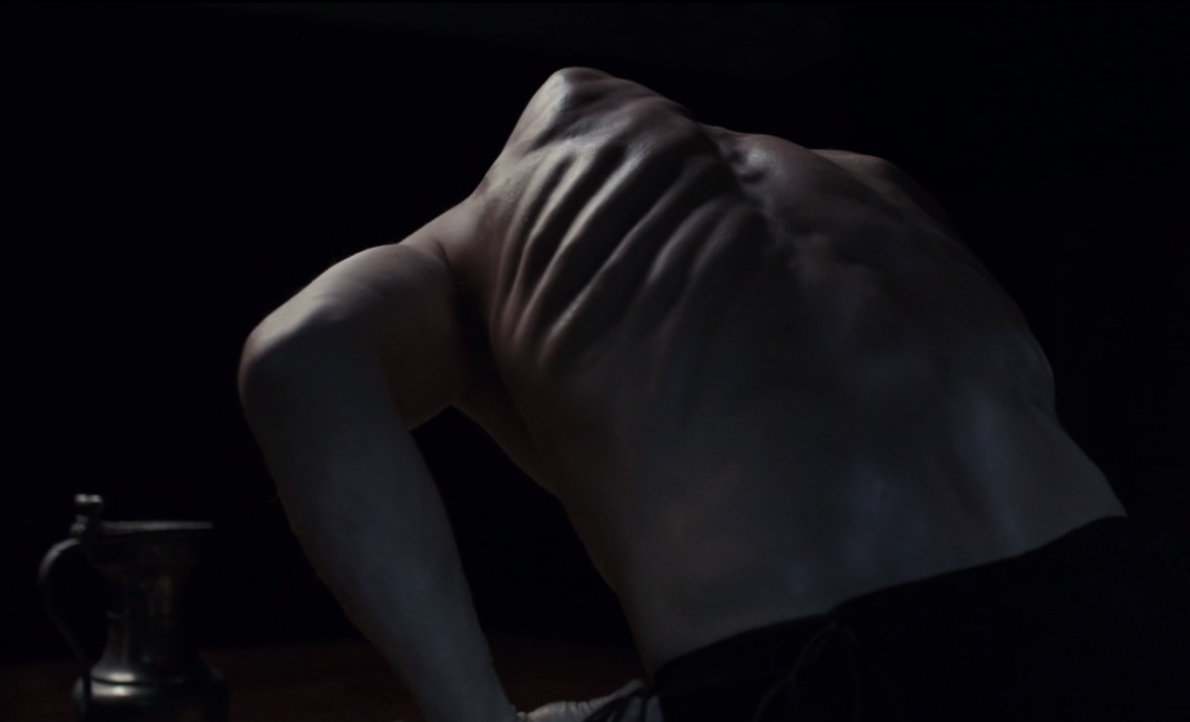

Having used “now is the winter of our discontent” to conclude the last episode, the finale opens instead with a Richard (Benedict Cumberbatch) in private, playing chess with himself rather than participate in his brother, the king’s, feast. The camera’s eye enters the room from behind Richard and very gradually pans for three-hundred and sixty degrees around his body before arriving on his direct address to the audience. The camera luxuriates in the combination of CGI and prosthetics required to depict a fully-exposed torso that is scarred, contorted, and flinching with occasional suffering. When we arrive at the soliloquy, it is full of spitting, chewing, and bile for emphasis, the payoff of which is to suggest that embodiment is linked to one’s moral compass.

Having worked with actors and directors, I have found that a contemporary production needs to make available the potential for empathy with Richard. First, it makes him more interesting by giving him an arc and, second, it disconnects one’s body from one’s moral worth. I was initially thrilled with Cumberbatch’s casting because I think his repertory rendition of the monster in Frankenstein, alongside Johnny Lee Miller at the National Theatre (2011), is one of the more important performances of the last decade. Certainly, there is a lot of the bodywork and choreography in this episode that made that Frankenstein so striking—and that’s a problem, I realize. Frankenstein’s monster has goofy wide pronunciations, an unsettled gait, and other interesting ticks that make clear he came into a body fully grown. Richard has lived every day in this skin, has adjusted and normalized his movements with time and aging. It doesn’t make sense for him to behave as if it is perennially new to him—except to suggest that when Richard’s body fails him, it is his embodied evil willing out.

Direct address soliloquies, for which this play in particular is so famous and the series has been structurally leading up to (with its cross-cutting and intimate POVs), provide the unique opportunity for audiences to get access to the interior of a character. It is the one moment when a play gives us a novelistic inside look into a character’s head. Better yet, soliloquies not only give voice to the unmediated moments where a character reveals what they really are thinking and struggling with, but also suggests the kinds of stories (kind of lies?) we like to tell ourselves in our most ambivalent moments. Despite the thoughtful use of the television format to structure perspective in the first two episodes, in this final episode The Hollow Crown utterly fails to make use of the direct address technique to problematize or render complex he that we would so easily cast aside. Why?

The episode is riddled with non-verbal direct address performances. These consist of several raised eyebrows or smirks to the camera right after Richard has told a lie, a dead-stop of tears once Anne has left his courtship, and a number of cross-cuts jumping from a close-up of Richard to suddenly sitting on the pommel of a knife blade then back again. At the point of deciding whether to pursue Bosworth Field, the camera lingers on Richard deep in thought. He turns abruptly, blinks, seems to recognize a camera there in shock and breaks frame of the scene and also of the episode. For a moment, all the postures change as if the actor Cumberbatch is realizing he’s been talking to my cat and I on the couch for the first time. Why?

In the second half of the episode, when the political set-up starts to crumble under his kingship, two non-verbal cues are repeated over and over again. First, Richard raps very loudly on the table with his ring of state, growing increasingly louder and faster to match his heartbeat as the tides turn against him. It is apparent to all of his cronies in the room as a sign of anxiety but not to Richard, exacerbating disloyalty. The body is willing out yet again, making apparent to everyone what he is thinking despite assuming he is well masked. Second, he is routinely surrounded by mirrors that wobble and fracture alongside his sense of (and his actual) power. By refracting his body back to him in these moments of political failure inherently links the two: a broken body so therefore a broken politics. Why?

Aside from the Jack Cade sub-plot, a number of other crucial moments have been cut from the series, including the drowning of Richard’s brother in Malmsey wine and the side-by-side battlefield visitations of ghosts to Richard and Henry Tudor. Director Dominic Cooke has on multiple occasions justified these by arguing that his aim was to examine “how many bad decisions does it take to put a psychopath in power, and anything that didn’t relate to that we got rid of.” It is a telling directorial vision: not only is Richard only a psychopath to Cooke, but one not worth even attempting to problematize or redeem. The treatment of the direct addresses and non-verbal engagements with the fourth wall now make more sense: Cooke was trying to give us access to the mind of a killer, like a period drama treatment of a true crime narrative a la Capote.

What is the point of a series that follows Richard from boyhood to death if it is going to provide a flat, expected villain? In truth, I had hoped that putting the adapted plays alongside one another would make abundantly clear that Richard is a product of a lifetime of cruelty and rejection aimed at him for the very thing he cannot control: his body. His mother, his siblings, every child, every woman he encounters mocks his body openly to his face. I don’t think it takes a post-Darwin world to suggest that a lifetime of rejection would produce this sense of self-hate and -harm:

I shall despair. There is no creature loves me;

And if I die, no soul shall pity me:

Nay, wherefore should they, since that I myself

Find in myself no pity to myself?

The soliloquies of Richard III make available such moments to not only sympathize for (that is, feel emotions toward the situation of) but empathize with (that is, feel emotions that echo the situation of) someone of an alternate ability. I wonder if we must wait for mainstream Hollywood to catch-up with compassionate and realistic depictions of a wide range of abilities before we get a compelling Richard for the silver screen, or if Richard already leads writers and directors to this new paradigm—if only they would follow. In this way, I hope the body does, in fact, will out.

Article Keywords: Premium.