Theater Reviews

Review of RSC’s Richard III

I twice sat in the stalls at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre to watch one fallen monolithic monarch memorialized, as the crown transferred to another.

The first time, on 19 September 2022, a silent, sombre, and subdued full house watched Queen Elizabeth II make her final journey from Westminster to Windsor. This venerated royal had ascended to the throne amid the turmoil of her father’s death and uncle’s abdication. She committed, at a young age, to serve her country, and did so for a record-breaking 70 years. The country, nay, the world, mourned her passing and now waits expectantly to see what her successor will do.

Just a few days later a post-Covid (for many it was their first time back in the theatre since the worst of the pandemic) anticipatory audience watched Richard, Duke of Gloucester, make his final journey from London to Bosworth. This reviled royal had ascended the throne through treachery and murder, turning his white rose of York blood red. He committed to rule his country for his own benefit to compensate for his deformity that, according to him, resulted in a life void of love. He ruled for a brief two years. In Shakespeare’s version of the story, mourners became revellers, rejoicing in the end of the vile king’s rule. It signified the resolution of the War of the Roses, as Henry VII and Elizabeth united the feuding houses of York and Lancaster in marriage.

The stark set presaged all the action of the next three hours. The thrust stage, which I could reach out and touch from my seat, resembled a blood-flooded field of dirt: a grainy, gritty texture mixed with deep crimson paint, and starkly empty, save for the cenotaph upstage. Designer Stephen Bronson and Lighting Designer Matt Daw bathed this notably lonely white monolith in red light to foreshadow Richard’s bloody path to the throne, his reign, and his demise. It also artfully announced to the audience that Lancaster red would ultimately prevail. The set further represented the play’s undercurrents: Richard’s royal seat sat atop a set of six stairs, while that of his ill-fated brother Edward sat on the floor, at eye level with his family and court.

The two-hour first act let the actors showcase their deep talents. Sparse sets and minimal movement allowed the audience to focus on them. Arthur Hughes, who I had the pleasure of seeing initiate his role as Richard in the Henry VI plays at the RSC last season, deftly filled these imposing shoes. The press has noted that this marks the first time a differently abled actor has played this king on this stage. As such, he and the director opted not to create an artificial back hump or limp. Instead, when he referred to his “deformity” (I.i.20), he drew attention to his own withered right arm. It added complexity and credibility to know that the actor himself had dealt throughout his own life with the challenges and triumphs of living with an attribute that made him different to others.

Hughes used complex facial expressions and physical movement patterns and pacing to convey his mood and motivations to great effect. His performance of Richard managed to command much more respect than did the monarch he played.

The women, too, took the stage by storm. Minnie Gale reprised her role from the Henry VI plays as Queen Margaret. Draped in crimson velvet, wearing a long, stringy grey wig to age her, she haunted the stage with a creepy, ethereal presence. She may call Richard a “bottled spider” (I.iii.241), but it was she who weaved a web of curses that eventually ensnared him. She crab-walked like the spine-chilling ghost that emerges from the television in The Ring. Her wails and moans belied her slight stature: she daunted even the mightiest.

Kirsty Bushel as Queen Elizabeth and Claire Benedict as the Duchess of York (Richard’s mother) provided strong-as-steel elements to this triumvirate of women that Richard wronged (Rosie Sheehy as Anne, too, was wronged, but did not give as notable a performance as the others). Their quiet, understated performances delivered a double dose of both strength and pathos.

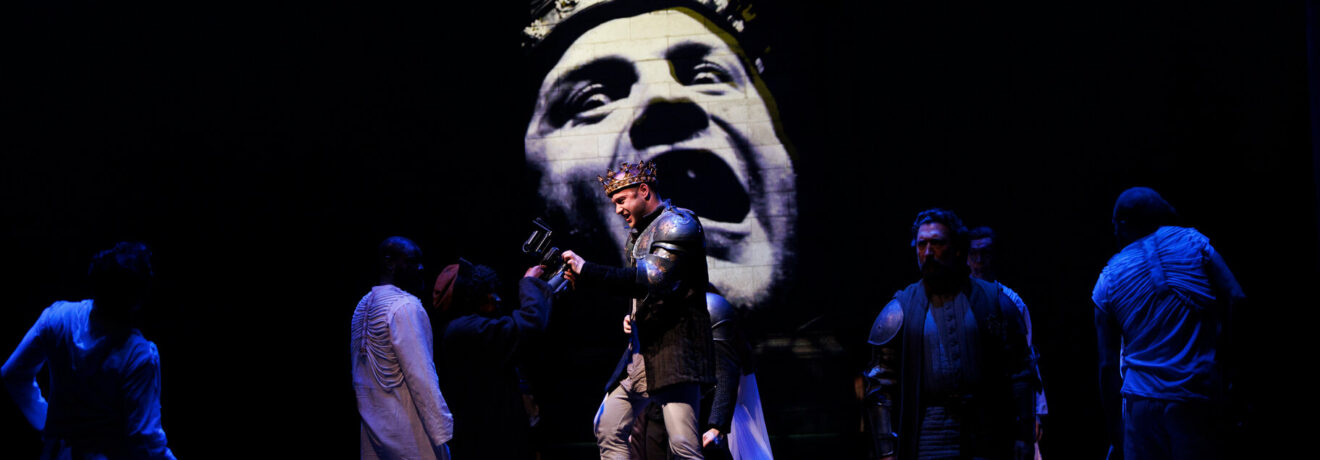

The hour-long second act ramped up both the levels of activity and theatricality; some to great effect, some less so. A handheld video camera (used, and equally confounding, in the Henry VI plays from the previous season) filmed both Richard and Richmond orating in real time in anticipation of the impending battle. A caped and cowled videographer stood squarely in front of each character in turn, blocking many audience members’ views. The speeches were projected onto the upstage monolith, angled toward stage right, making it – again –impossible for certain sections of the audience to see. This use of very modern technology in a production otherwise grounded firmly in the 15th century felt jarring and out of place. Other than making the adversaries resemble modern-day political adversaries (a point that needed no underscoring) added nothing to the play’s themes and served only to take me out of the otherwise engrossing action.

Conversely, the lower-tech but extremely creatively imagined wispy-white-clad ghosts of Richard’s numerous victims haunted his dreams. They coalesced in balletic movement to form a horse to lift Richard up and drop him to the ground as he begged for “a horse, a horse.” (V.iv.7) This compelling visual provided a fitting metaphor for the victims’ impact on his fate. They formed a diaphanous phalanx with Anne at the front of the “V,” her flaming red hair providing an aptly colored mane. Finally, they elevated Richmond, victorious, allowing him to ascend to the throne on the shoulders of Richard’s victims.

I twice sat in the stalls at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre to witness the historical changing of the guards. In the first case, a country celebrated a steadfast and devoted monarch. In the second, those on stage and in the audience celebrated the demise of a misguided and power-hungry monarch. Both performances were moving and conveyed important, timeless messages. Most prominently, seeing these two events in close proximity highlighted how an outward-facing focus, with hte good of the many prioritized over the good of the few (or the one), always triumphs.

Notes:

[i] For instance, see https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2022/jul/01/richard-iii-review-rsc-stratford-arthur-hughes.