Reflections and Essays – 70.1

Shakespeare on Screen: Coronavirus Edition, Part Two

“Part One” (69.2) showed that the American Shakespeare Center and the Flatwater Shakespeare Company streamed subprofessional video captures during the 2020 pandemic, which is having its 2021 Delta surge as this is revised. The Oregon Shakespeare Festival and the Barn Theatre did rather better with videos created for marketing purposes then edited for streaming, but even these films suffer when compared to videos by theaters with inventories of performances already screened in cinemas and released on DVD. Other theater companies went a different way by reading Shakespeare on Zoom, the subject of Part 2. Part 1 attempted to cover all plays streamed by professional companies. Part 2 originally shared that goal, but the high number of readings accumulating as part one was written limited me to performances with high media coverage, the readings most likely to be the subject of future study. Part two identifies those companies, the plays produced, gives background on the people who organized the readings, and the reasons for producing these readings. As before, I hope that presenting these facts will give scholars a place to begin work on these performances in the future. The St. Andrew’s Players and Play in the House performances, considered first, are straightforward readings of two Shakespeare tragedies. The others are political readings. The Show Must Go Online (TSMGO) promoted non-traditional casting with mixed results and the Public Theatre fused the Black Lives Matter movement to its dramaturgy. One must have a cutoff, or this article will never be finished. As before, that is September 2020, though some information learned later is included. All these performances were recorded and may have afterlives unknown at this time.[1]

St. Andrew’s Players/King Lear

The reading with the most star power is King Lear with Stacy Keach. Lear was presented by a theatre company affiliated with St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Yardley, Pennsylvania, the St. Andrew’s Players. Director Gary Sloan told me that St Andrew’s had been producing entertainments since the eighties, usually during the holidays, but in its current form the Players “officially began when Robin Prestage, parishioner and native from England, asked me to play Scrooge in A Christmas Carol reading in 2018. A production comprised of professionals in the church and talented parishioners, including my son as Tiny Tim!”

I wondered who ultimately signed off on performing Lear on Zoom. “It was our Priest Hilary Greer who inspired the project. She wanted something that reached out, shared the important story of Shakespeare’s own history with plague and Lear, and it’s message for our times.” James Shapiro has shown that Lear was not written in a plague year, but this misinformation was commonly mentioned in media and social media during 2020, so the mistake is understandable.[2] Donations were solicited for the Bucks County Housing Group Community Food Pantry at Penndel, PA, the show interrupted for a brief appeal for donations halfway through with another given after the performance. Greer invites viewers to visit the church in a short preamble before Sloan introduces the play.

Sloan has been a professional actor for forty years in Los Angeles and New York. He has a few television and film credits but more frequently works in leading regional theaters, including in Washington D. C. where he has several Shakespeare credits. “I did three Lears in one year, twice with Hal Holbrook, Cleveland and off Broadway at the Roundabout, and then once with Fritz Weaver at the Folger in D. C. (11 grueling mud – filled weeks!), and now with Stacy Keach on a Zoom LIVE stream across the nation! But let me also say, that the spiritual connections were profound. 30 years ago, to the day, April 23, Ed Gero (our Gloucester), Dan Southern (Edmund), and myself as Edgar opened Lear at the Folger in 1990. Ed and Stacy had done Lear together in Chicago and D.C. Stacy and myself bonded when he visited Tudor Hall, Bel Air, MD – the famous Junius, Edwin and John Wilkes Booth homestead where I was actually living and working to support at the time. This Lear, inspired by our little giant church of players, was a grand reunion in every direction,” and we note that the performance date was on Shakespeare’s traditional birthday.

How many actors were pros and how many were amateurs? “With a cast of 16, we enlisted and were approved by Actors’ Equity Association to include 8 professionals (3 of us with St Andrews); the others from various professional connections over the years, and 8 talented non-professionals.”

I noticed that the running time was 2 hours and a minute, and the first seven and a half minutes is a shot of the title before the performance is introduced. Who cut the text for this performance? “I did, with a little assistance from Ed Gero and Stacy Keach and Sabrina Profitt (Goneril). But, but, but, it’s actually around 1 hour 45 minutes – the streaming intros and slides made it longer … we basically ‘borrowed’ from the Peter Brook, Orson Welles cutting they used for a CBS Omnibus presentation with Alistair Cooke in 1953, also LIVE television. But I added the Gloucester, Edgar, Edmund subplot back into it … so it was an adaptation of an adaptation.” The all-volunteer show was streamed live on the St. Andrew’s YouTube channel, then was available for four days before removal by agreement with Actors’ Equity. The amateurs are obvious even without consulting the credits, which note the Equity members, but they are not hopeless and the Equity actors give excellent performances with Daniel Southern a standout Edmund.

The short-term goal was to put on a show with parishioners and professional actors to support the food bank. Was there a long-term goal? “We wanted to spread the message of a welcoming, inter-faith, LGBT friendly, creative Christian message during tough times.”

I asked Stacy Keach about his history with Lear. “My very first experience with the play was as a student at London Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts in 1964, when I played Kent. My fellow student and pal, Andrew Robinson, played Lear, and he had one of the most memorable faux pas when he uttered: ‘How sharper that a Soopent’s Terth to have a thankless child!’ My first professional Lear was in the 1968 production at Lincoln Center, starring Lee J. Cobb, directed by Gerald Freedman. I played Edmund. I played the title role in a wonderful production directed by Robert Falls at the Goodman Theater [Chicago], in 2006. This same production was repeated at the Shakespeare Theater in Washington, DC in 2009. Our Zoomed production featured Ed Gero as Gloucester, a role he played in the Robert Falls production. I was very pleased to have worked with my daughter, Karolina, for the very first time. In my totally unbiased opinion, she was a wonderful Regan!” She is a good Regan, and fortunately for her father, not a method actor.

I asked Keach if there were unusual challenges performing Lear or any play online. “Zoom theater presents a whole array of challenges that are unique. Each actor is his own sound man, cameraman, and stage manager. One of the keys to achieving a successful performance lies in the actor’s ability to scroll his script with one hand, while keeping his eyes on the little green dot at the top of the computer (where the camera is). It’s very distracting to see the actor’s eyes looking up and down as he or she reads the text, so the challenge becomes similar to a stage performance in that the more familiar the actor is with the lines, the better the ability to play to the camera, or the audience.” Performing the play for the third time gave Keach a leg up.

I mentioned that his Lear was forgetful in the first scene and that his character is written to skip from subject to subject in some latter scenes. “Lear’s dementia is fueled by his overweening ego, which tramples over his ability to maintain any semblance of rationality when he feels threatened or under-adored. Remembering the names of his daughters’s suitors has no priority whatsoever in his mind. They are minions unworthy of his attention. By the time we arrive on the heath in the storm scene, his wits have brought him back to childhood, where he can smother whatever pain and anguish he is suffering in the cradle of childish innocence, but reality keeps popping up, causing him to embrace another strain of forgetfulness with greater passion, as an escape from the plight he has created for himself. The depth of the tragedy is amplified in the later scenes when he comes to the realization of his folly, and this is where Shakespeare’s genius really kicks in with that futile recognition.” I am grateful to Mr. Keach for these comments and that he is not one of those actors who hides behind the claim that the work speaks for itself. If it did, we would not have questions.

Keach went on to found the Stacy Keach Zoom Theatre with six non-Shakespearean productions to date, all benefits for The Actor’s Fund.[3]

Disclosure: I have known Stacy Keach for several years.

Play in the House/Macbeth

Slone told me about a Zoom performance he hoped to direct at the end of our King Lear interview, “I’ve communicated with Patrick Page, a wonderful classical actor, currently paused from Broadway’s Hadestown, about doing a Zoom Macbeth for #Playsinthehouse. We’re in serious discussions about it and I’m hoping to begin rehearsal and casting very soon.” The performance Zoomed on 13 June.[4]

Stars in the House began in March as a series of short Zoom performances and interviews hosted by Seth Rudetsky and James Wesley to benefit The Actor’s Fund.[5] $50,000 was raised in the first four days.[6] Play in the House (PitH) was added the next month, Saturday afternoon Zoom plays readings beginning with a reunion of the original cast of Wendy Wasserman’s The Heidi Chronicles, the Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award winning play first staged in 1988. Macbeth is the only Shakespeare play performed by PitH.[7]

Sloan hoped to repeat the recorded King Lear, but PitH wanted a live performance and asked Sloan if he could remount the play. PitH, unfortunately, could only accommodate eight computers, which “simply left Lear out of the question … but they were interested in a Shakespeare and asked if I could think of anything else – and having played Macbeth as well as directed it in NY State prison, I was very familiar with it and thought it would be an ideal choice with actors doubling and perhaps cutting out some of the smaller scenes/characters. Plus, it was also one of Shakespeare’s ‘plague plays’ which he wrote while theaters were shut down, an added connection.

“I was aware of Patrick’s work at places like Utah Shakespeare and I saw him in a production at the Public, too. Patrick played Macbeth at Shakespeare Theatre Company when I taught at Catholic University of America in Washington D.C., and I asked him to teach a master class at CUA which he agreed to do – and so I got to know him better and over the years, became increasingly aware of his work in D.C. and New York City. So, when the idea of a Macbeth was considered for Plays in the House, I thought Patrick would be ideal casting and he agreed that the camera would be a new and interesting approach to the play.”

Sloan liked Page’s suggested actor for Lady Macbeth. “I had gotten to know Hannah Yelland at a reading in DC and loved her, so we reached out to her and although she was in London lockdown, she agreed.” Page also found some others in the all-professional cast. “Everyone was happy to work with him and especially support this platform.” The eight-computer limit led to “choosing couples to play different parts in order to have more actors use fewer computers, thus allowing more characters under the live stream restriction.” Yelland’s actor father, David Yelland, played King Duncan. The actor playing Ross/bloody sargeant/Porter (Sherman Howard) is married to Lady Macduff (Donna Bullock). Sloan was Banquo and his son Owen played Fleance and Macduff’s boy. This allowed 11 actors to use eight computers.

Sloan also “had to accommodate Zoom fatigue, viewers becoming impatient with sitting in front of their devices for a long period of time.” What he called “large cuts” were made in the dialogue between Macduff and Malcolm in 4.3, a scene reduced in many productions, and in what Sloan calls “the many soldier scenes toward the end.” This production was a benefit for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Macbeth has a few sound effects and a dash of music, both credited to Ryan Rumery. Here is an incomplete list of the props, costumes, lighting, and makeup: the single murderer (Rachel Crowl) wears a hood, Page manages some lighting effects including blowing out a literal brief candle at the end of that speech (5.5.16-27), holds a dagger at one point, and holds a glass of wine during parts of the banquet while two of the other actors also hold glasses for the toast. Banquo has blood on his face, neck, and down his chest when he appears as the ghost. Many of the actors, especially Page, take advantage of the microphones built into their computers to speak softly and even whisper at times. This would not work on stage but projecting as in a large theater would overwhelm Zoom listeners. One of the actors, Ty Jones as Macduff, is the exception. He bellows his lines, failing to understand that in Zoom readings less is often more. The rest of the cast is marvelous, and Page is one of the strongest Macbeths I have seen.

Sloan concluded his messages to me with this interesting thought. “Imagine telling Shakespeare that one day, 400 years later, there is another plague, theaters are closed, but an actress will be in London and an actor in NYC across the ocean, will be playing scenes from Macbeth, able to see one another, hear one another at the same time and be seen by anyone in the world! That’s what we did.” As with King Lear, PitH was not able to keep Macbeth online due to an agreement with Actors’ Equity.

So far, so good, and I do mean good. The Sloan directed readings are not above criticism in part because of some unevenness in the cast of King Lear. Both casts nevertheless delivered straightforward, and in the case of Macbeth, professional readings of Shakespeare’s plays. The companies considered below had other approaches and priorities, with wildly different results.

The Show Must Go Online/The First Folio Plays and More

TSMGO, as they usually call themselves, has the cleverest company name I have seen in a long time. The company is the brainchild of Robert Myles, Sarah Peachy, and some of their friends. They initially claimed to have produced Shakespeare’s complete plays while only producing the First Folio plays, knowingly skipping recent attributions such as the collaborations Edward III, Arden of Faversham, and initially skipped the longer established collaborations of Pericles Prince of Tyre and Two Noble Kinsmen, though Henry VIII was performed because it is in the First Folio. Performances were given once a week from March to November in the order the plays were written according to the “Chronology of Shakespeare’s plays” Wikipedia page[8] they claimed, though that chronology was fudged to present the Henry VI plays parts 1, 2, and 3 in that order and TSMGO privileged the inaccurate tradition that The Tempest was Shakespeare’s last play by performing it last.

Anticipating the shutdown of live performances, TSMGO had Two Gentlemen from Verona in rehearsal when London theatres closed on 16 March, according to an article on the Folger Shakespeare Library website, which also explains that “each play is judiciously trimmed to eliminate racist and intolerant language that doesn’t serve a thematic purpose, as well as some Latin and obscure allusions to Greek and Roman myths.” Male roles may be cut entirely, but due to its “commitment to gender parity in its casting, no women’s roles are cut.”[9] This is puzzling because TSMGO casts gender blind with many women playing men’s parts. Some original Shakespeare themed cabarets were also presented.

TSMGO took a break after November but surrendered to requests by listeners and some of the creatives to produce Shakespeare and Wilkins’s Pericles, Prince of Tyre in February 2021 (which they attributed to Shakespeare alone), John Lyly’s Gallathea in April,[10] and Marlowe’s Edward II, Doctor Faustus, and Dido Queen of Carthage (attributed to Marlowe alone) with a Marlowe-themed cabaret in June.

TSMGO viewers conceived a patronage plan after the first show. The form changed a little over time, but patrons eventually paid an amount of their choosing with a minimum of $1.00, renewable monthly, though patronage may be cancelled. This gave members access to these later performances, a weekly sonnet reading, dozens of photographs, and other content. The money was divided between the creatives.[11] As of 7 July 2021, there were 194 patrons giving $1355 monthly. The funding for TSMGO was suspended later that month as TSMGO rethinks its funding model.

All plays begin with a welcome, introductions by academics, commentary during a brief intermission, and end with post-show comments and what would be called a talkback in a theatre. Some of this was facilitated by David Crystal, known for his work on original pronunciation, though modern pronunciation is used in TSMGO performances.

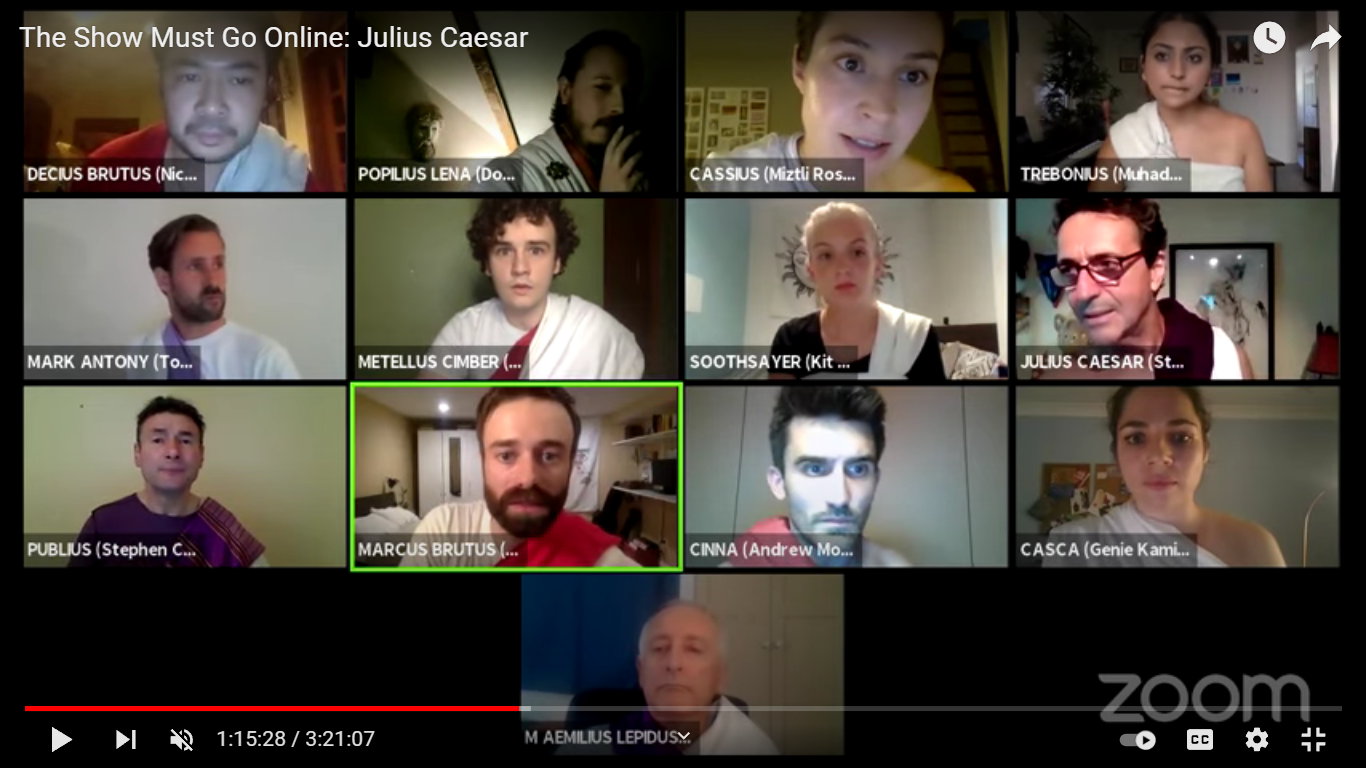

Most TSMGO readings include visual elements. The cast wear toga-like costumes for Julius Caesar and while none were in the same place, when Poplius whispers to Caesar, actor Dominic Brewer leans to the edge of his screen to speak quietly to Stephen Schnetzer’s Caesar, who leans slightly towards Poplius. The two images are not adjacent on Zoom with Brewer and Schnetzer in different rows, so this visualization fails. In plays with characters handing letters or other documents to one another, actor 1 hands a paper past the screen and actor 2 takes what is intended to be the same paper and brings it on screen. I wondered about rehearsal time since these visuals must be coordinated. Myles told me that the First Folio plays “rehearsed for approximately two and a half days. Later rehearsals were longer now lasting about a week to give new directors additional time to interpret the form while pushing the innovation of this work forward.” Cameras are static; the only movement is by one character within the space of the camera. Mostly, the actors look at their computer screens instead of each other as they would on stage. Many declaim their lines, perhaps because they do not interpersonally connect.

TSMGO won some minor awards and was widely covered in the press. Myles told the Broadway World website this is due to Shakespeare “as a unifier” and his power to speak to our essential humanity.

Who mounts and who watches TSMGO performances? Myles told me, “From March 2020 to now,[12] over 500 creatives from 6 of the 7 continents have volunteered to create 46 full-scale digital productions (40 of those done in 36 weeks in 2020) and 50 sonnets, for a total creation of over 140 hours of content, for a global audience of over 200,000 views. This movement inspired careers, created international friendships, and for some artists, saved lives and gave them meaning. Autistic children have been able to engage with this experience on the same terms as everyone else because the flatness of the medium has eliminated the sensory overload of a traditional auditorium. People in palliative care have spent some of their last hours engaged in meaningful shared experience on the same terms as the rest of the community, feeling a part of something while cut off from any direct contact, even with family members.”

Myles has a history with Merely Theatre, which practices non-traditional casting and TSMGO follows that practice.[13] Myles told Broadway World that he did not “come to Shakespeare with the same presumptions or barriers as some people when it comes to casting” and that TSMGO tried “as many global majority actors involved as we can … even if they don’t have loads of Shakespeare experience.” The lack of experience shows, so I asked how parts were cast.

“For the First Folio we had a mailing list that actors subscribed to in order to receive weekly casting calls, which at its height had about 2,800 recipients. Castings were submitted using a form, the data from which was then automatically populated into a casting database for the weekly show, which included details for the applicants including number of times applied, number of times cast, level of experience, access needs, and more. Performers of any skill level are invited to submit and send us information about themselves, their interest in the play, and any relevant skills/experience they have. The director will then put together a cast of a diversity of experiences, nations, and identities. We never auditioned for The Show Must Go Online, instead taking chances and making discoveries as we go. We are proud of the progressive casting we have been able to achieve, and always strive to continue to show that Shakespeare is for everyone, by everyone.”

Myles sees this as educative because a few of the actors have worked for the Globe, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the National Theatre, in the West End, on Broadway, and with the Reduced Shakespeare Company, so “getting those veterans present in the room, working the way they work while there are far less experienced people sharing that space with them and getting to see this is how it’s done. Our far less experienced actors have gotten to see best practice in action.” I found no stars in the casts, though Simon Russell Beale, a successful Timon of Athens in at the National Theatre in 2012, helped TSMGO introduce that play.

Nurturing less experienced actors is fine when listener expectations are low. Unfortunately, mine were high. TSMGO cast widely but not well. Many actors, perhaps most, seem miscast or are simply bad in their roles. Myles told Broadway World that the best shows the company has done are Richard III, Hamlet, and Macbeth “from a pure quality perspective, and proof of concept perspective – this medium works, and trying to take as much advantage of various features as possible.” These three may have used Zoom better than the other TSMGO readings, but I thought they were awful.

I said none of this to Myles, who nevertheless read between the lines of my questions and assumed I am harder on TSMGO than I actually am. He scolded me about this and several other things. “I encourage you to view the work in context: volunteer- and values-led, with no budget and little time, produced relentlessly during a time of global chaos, focused on global communion around shared passion, surprise and delight; sharing that same passion with traditionally excluded and underrepresented groups by creating work with unprecedented accessibility, both for audiences and performers.” I see this as an elaborate rationalization. Myles argument for inclusive casts could be convincing if TSMGO delivered excellent readings by diverse but better actors. It is great that so many people used TSMGO to deal with problems of isolation and all the bonding must be celebrated, but better actors would have erected a bigger tent where those of us with quality standards would also feel welcome. Mediocracy impairs the message. Myles is proud of what TSMGO accomplished. They accomplished a lot but could have accomplished more.

Myles announced on 21 July 2021 that TSMGO will be suspended. It was too time consuming for him and the team to continue producing at the rate they had even at the slower pace in 2021, so the leadership paused to consider if they should continue. It also announced that The Two Noble Kinsmen would be the last TSMGO show. It Zoomed on 8 September.

Public Theater/Richard II

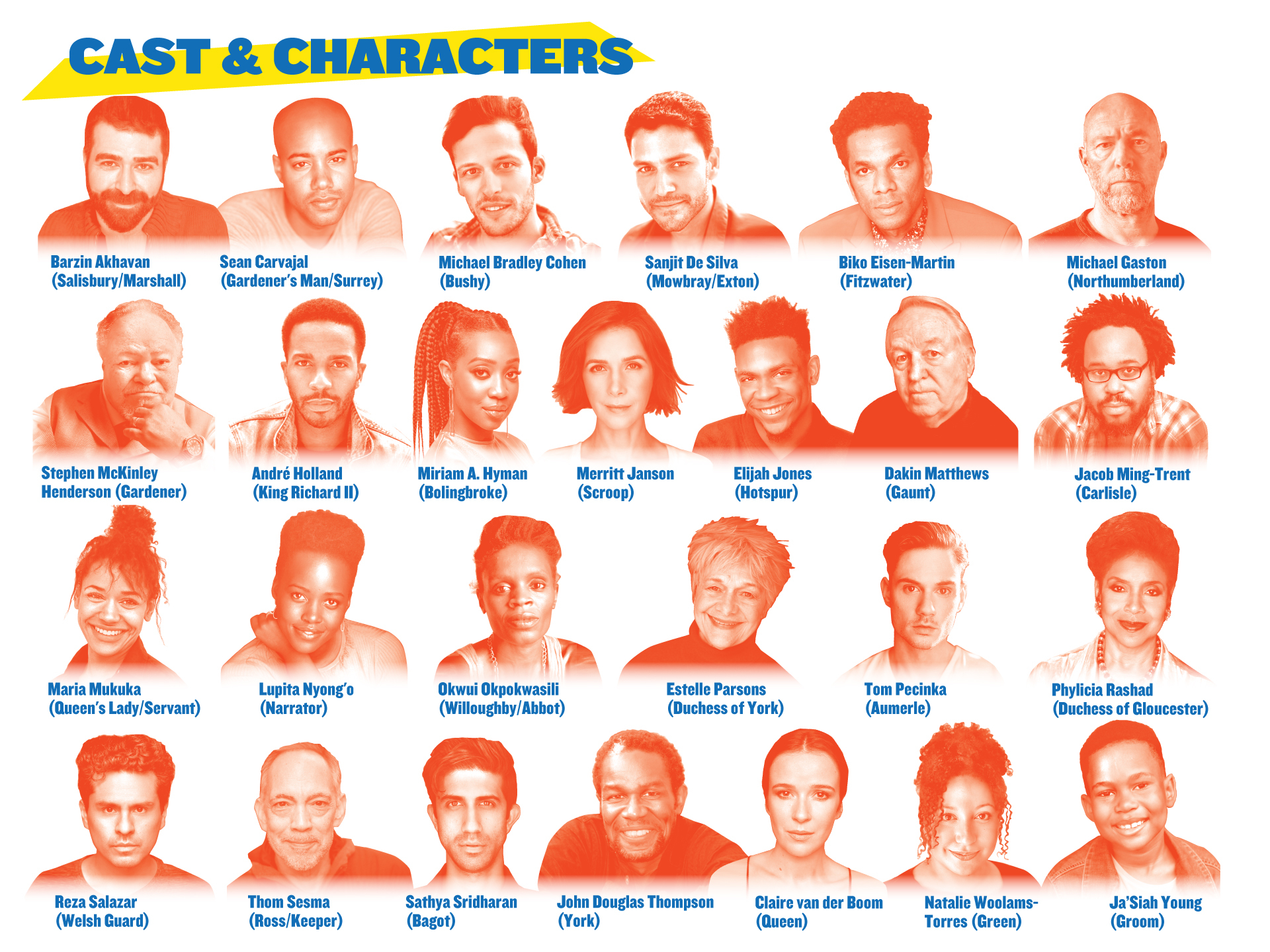

TSMGO didactically imposes a mass inclusiveness on early modern plays. The New York’s Public Theater imposes a narrower inclusiveness on Richard II. Kenyen born director Saheem Ali already planned a politically challenging production on the Delacorte stage and cast accordingly. His Richard, André Holland, spoke of his fascination with the deposed King’s last act soliloquy, telling the New York Times, “I’ve been chomping at the bit to say those words for so long. They invite the audience to see a Black man becoming more vulnerable with himself.”[14] Holland and Ali were concerned about the casting of the usurper Bolingbroke, fearing the optics of a competent White leader replacing an incompetent Black leader and the possible prejudices that might reinforce for some people. That problem was solved by casting African American Miriam A. Hyman as Bolingbroke. They did not, however, anticipate that the death of George Floyd would fuse with their work.

The 19 May opening was cancelled by the pandemic, of course, and then Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on the 25th. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) organization was founded in 2013 as a response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin in 2012. BLM and others protested this and subsequent killings of Black men and women in the intervening years, but the nearly nine minutes of video showing Chauvin murdering Floyd awakened consciences as nothing else in living memory and caused protests across the country and to a lesser extent abroad in England, Brazil, France, Germany, Mexico, Poland, and Syria, to give an incomplete list of countries.

The Delacorte staging was off and BLM protests on when the offer came from National Public Radio station WNYC to air a serialized version of the play. It was a way to keep the show alive but nobody on the creative side had experience making radio drama, and there was a bigger problem. Did the play still matter?

The first radio rehearsal was conducted via Zoom, as the recordings would later be. That rehearsal became what the director told the Times was “a virtual town hall, some of the cast expressing doubt that the play was worth pursuing. What does an old white guy from 400 years ago have to say to me right now?” One member of the cast was not persuaded the play was worth doing and left the show,[15] but Holland’s passion for his role helped others see Richard II as a way to expose the full humanity of Black people to listeners. Hyman said that being Black and a woman makes her a member of the most disinherited group of people in America, and that gave her insight into playing her disinherited character.[16] Much discussion was given to accents, rhythms, and diction so that listeners could identify the Black characters as Black. Thomas said that when he was not recording, he listened in just the hear the actors express “their lives through these characters.”

These matters went to the very heart of the Public Theater. On the episode “The Arts Interrupted” that aired on the 14 May 2021 Public Broadcasting Service television series Great Performances, Public Theater Artistic Director Oscar Eustis said that his theater did not want to be a center of systemic racism. After the death of George Floyd and the protests that followed, the Public looked at what it should become, “we need to give agency to those who have been denied agency historically in this country,”[17] and in a 15 May 2021 live chat titled “Shakespeare and Politics,” Eustis answered my question about the politics of this Richard II by saying, “what we have done is embed the discussion of Richard II in a production of Richard II.[18]

Richard II was planned as a modern dress staging so audiences would apply the ideas in the play to today. Ali told the Times that he found audio equivalents for much of what he had intended to do visually. The audio narrator tells listeners that the dying John of Gaunt (Dakin Matthews) is in hospital. We hear the frequent beep of his monitor. The speed of the beeps increases during Gaunt’s final lines, then become a continuous tone to indicate his death. Northumberland (Michael Gaston) gives his 3.3 lines from a distance using a bullhorn. A radio news report is heard announcing Bolingbroke’s usurpation in 5.2, which leads to York (John Thomas Johnson) telling the Duchess (Estelle Parsons) the details of the conspiracy that involves their son Aumerle (Tom Pecinka), then Aumerle speeds to Bolingbroke on a motorcycle. These are a few of the many sound patterns that place the story in our time.

The script was divided into four parts with the play text taking about 35 to 40 minutes in each 58-minute episode. Richard II is obscure to most audiences today. Why are Bolingbroke and Mowbray so angry and who is this Gloucester that Bolingbroke accuses Mowbray of killing? These are just the initial difficulties unexplained in Shakespeare’s dialog. Ali uses narration before each episode to explain such difficulties and occasional additional narrative when needed between scenes and lines to keep the motives, characterizations, and action clear. New Yorker writer Vincent Cunningham interviews some of the principal actors and backstage people as each episode opens and closes, especially Ali, Holland, Hyman, and consultants James Shapiro and Ayanna Thompson. These interviews present Richard II as a drama about racial justice. These broadcasts are the clearest presentation of the play I have enjoyed but also the production with the narrowest range of interpretation. It is problematic to reduce the nuance of any Shakespeare play to a slogan as these broadcasts do, but the message needed in America today.[19]

Ayanna Thompson was thrilled by the production, saying near the end of the second episode, “I love it so much and I think it will open another way for us to think about how we understand race and how we understand culture, because what I love about the actors’ voices – I love the fact that these actors sound so American and sound Black, sound like Black Americans, and it made the words clearer to me. I felt like I was hearing the words in the most clear fashion imaginable.” I have no problem with that statement.

I have not had Thompson’s life experiences and as a grouchy old white man must not judge her, but she made another statement that seems questionable. “I left this production feeling like Black Americans should be the ones doing Shakespeare from now. (Laughter) You’re welcome, America, again.” Perhaps the laughter is a clue that this was intended as a joke. It is not funny.

Dr. Thompson might consider how this would sound to her if a white person said the same thing about white actors, as many unfortunately have and do, or if someone from any other community of color said it about their own community’s actors. I trust Dr. Thompson agrees that Shakespeare belongs to everyone.

Disclosure: Dakin Matthews was my undergraduate Shakespeare professor.

The Sloan led productions are strong traditional readings of heavily edited texts. This is not true of the Public Richard II which is a strong non-traditional reading of that play or The Show Must Go Online readings, which are neither traditional nor strong. It is admirable that all these companies and those considered in Part One found ways to produce some income, gave work to actors and others behind the scenes, and made Shakespeare performances available when theaters were closed. It is too early to know if streaming and Zoom Shakespeare is merely a stopgap measure until theaters reopen or if these readings are a new way of performing, as Robert Myles believes. Time’s pencil will write the answer.

Zoom performances covered in the article.

Play in the House

- Macbeth, 13 June

Public Theater

- Richard II, 13-16 July

The Show Must Go Online

- Two Gentlemen of Verona, 19 March

- The Taming of the Shrew, 26 March

- Henry VI, Part 1, 1 April

- Henry VI, Part 2, 8 April

- Henry VI, Part 3, 15 April

- Titus Andronicus, 22 April

- Richard III, 29 April

- The Comedy of Errors, 6 May

- Love’s Labour’s Lost, 13 May

- Richard II, 20 May

- Romeo and Juliet, 27 May

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 3 June

- King John, 10 June

- The Merchant of Venice, 17 June

- Henry IV, Part 1, 24 June

- The Merry Wives of Windsor, 1 July

- Henry IV, Part 2, 8 July

- Much Ado About Nothing, 15 July

- Henry V, 22 July

- Julius Caesar, 29 July

- As You Like It, 5 August

- Hamlet, 12 August

- Twelfth Night, 19 August

- Troilus and Cressida, 26 August

- Measure for Measure, 2 September

- Othello, 9 September

- All’s Well That Ends Well, 16 September

- King Lear, 23 September

- Timon of Athens, 30 September

- Macbeth, 7 October

- Antony and Cleopatra, 14 October

- Coriolanus, 21 October

- The Winter’s Tale, 28 October

- Cymbeline, 4 November

- Henry VIII, 11 November

- The Tempest, 18 November

- Pericles, Prince of Tyre, 15 February 2021

- Gallathea, 21 April 2021

- Edward II, 9 June 2021

- Dido, Queen of Carthage, 16 June 2021

- Doctor Faustus, 23 June 2021

St. Andrews Players

- King Lear, 23 April

Notes

[1] Sheila Cavanagh looked at two other Zoom performances that do not fit my criteria in the previous issue of Shakespeare Newsletter, 69:2, Spring/Sumer 2000: “’Spirits from the Vasty Deep’ and Beyond: Shakespeare in the Age of Zoom – The Shakespeare Newsletter

[2] James Shapiro, “The Shakespeare Play That Presaged the Trump Administration’s Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic,” The New Yorker, 8 April 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-shakespeare-play-that-presaged-the-trump-administrations-response-to-the-coronavirus-pandemic

[3] SKZT Presents Barrymore | April 25, 2021 | Mysite (stacykeachzoomtheater.com)

[4] Subsequent Sloan quotes will be from a series of later emails about the Macbeth reading.

[6] About Us | Stars In The House

[7] https://www.starsinthehouse.com/plays-in-the-house

[8] Chronology of Shakespeare’s plays – Wikipedia

[9] “In the brave squares”: The Show Must Go Online – Shakespeare & Beyond (folger.edu)

[10] The Show Must Go Online Presents: Gallathea by John Lyly – YouTube

[11] THE SHOW MUST GO ONLINE – Robert Myles (robmyles.co.uk)

[12] Email dated 7 July 2021.

[13] The most recent information on the Merely Theatre website dates to 2018. I wrote asking if they were out of business, but no reply so far. Merely Theatre – Professional theatre company creating energetic, stripped-back Shakespeare

[14] Bahr, Sarah, “The Public’s ‘Richard II’ Finds New Life,” New York Times, 10 July 2020, p. C6.

[15] I do not know the name or ethnicity of this performer. Not everyone in the cast was African American.

[16] This was said in an interview that was part of the first broadcast.

[17] #PBSForTheArts | About The Arts Interrupted | Great Performances | PBS

[18] Shakespeare and Politics: An Interview with Oskar Eustis – YouTube. Eustis did not know I was writing this article and so was could not have been shaping his answer to its needs.

[19] All episodes may be heard here: https://publictheater.org/media-center/series/richard-ii/richard-ii/