Premium Content

Talking Books Update (73)

From the Domesday Book to Shakespeare’s Globe: The Legal and Political Heritage of Elizabethan Drama, Berpols Publishers, 2023.

First up is this book by Dominique Goy-Blanquet, which I found challenging because I have never studied the interrelatedness of English jurisprudence and early modern English drama. Her book argues that England asserted cultural, legal, and artistic independence from the continent, studies conflicts between the independence of individuals and the authorities who govern them, and demonstrates that dialog between different legal forces began before the theaters opened. “Resistance to tyrants runs like a red thread, or red threat, through successive constitutional theories” (22).

Goy-Blanquet’s expounds differences between English and French legal thought then surveys the first Tudors through Mary Stewart, especially noting that the rise and fall of monarchs prefigure the dramatic structure used by playwrights. Many of the legal issues debated were dramatized as various characters, themes, and even metaphors by Elizabethan era playwrights. She next examines the change as religious leaders, once promoters of plays that advanced their causes, became critics when messages in the plays changed. New and potentially dangerous ideas of commonwealth were enacted on stages as similar ideas evolved in Parliament and the Inns of Court.

Shakespeare gets the most notice in this last section, with his history and Roman plays giving poetic voice to these ideas, but there are approximately 350 contemporary works cited throughout the book including other plays, masques, legal acts, statues, treatises, poems, and dialogues. This learned and fascinating book opened new horizons for me.

Shakespeare: The Critical Edition King Lear, Arden Shakespeare, 2023.

Shakespeare: The Critical Edition King Lear, Arden Shakespeare, 2023.

My fourth “Talking Books” guest Sir Brian Vickers supervised the editions of two quite different books. He and Joseph Candido are the series editors of Shakespeare: The Critical Tradition collections of historic essays about each of Shakespeare’s plays. The King Lear volume is edited by Kevin J. Donovan. The one-hundred readings range in date from 1799 to 1922. Donovan’s introduction sets these readings in context starting with Lear criticism prior to the first piece in this collection, then surveys the criticism in the 132 years excerpted in this book before studying criticism from 1922 to the near-present.

The essays and excerpts include such well-known commentators as Leigh Hunt, Edmund Malone (in an excerpt from his chronology, see Tiffany Stern’s book below), Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlett, Charles Lamb, John Ruskin, Algernon Swinburne, Frederick Boas, A. C. Bradley, Leo Tolstoy, Walter Raleigh, A. E. Taylor, Frank Harris, E. E. Stoll, and C. F. Tucker Brooke. If your reaction is, “the usual suspects,” that is the point. This collection brings together the classic essays in Lear criticism in one place along with others less well-known. Some of the ideas expressed are museum pieces we have moved beyond, but others should provoke reconsideration. This is a good book to have in your university library.

The Collected Works of John Ford: Volume IV, Oxford University Press, 2023.

The Collected Works of John Ford: Volume IV, Oxford University Press, 2023.

Vickers also oversees The Collected Works of John Ford. It has been six years since the publication of volumes II and III on Ford’s collaborative plays. Volume II published authorship introductions and authorship commentaries and volume III published the six collaborative plays with standard introductions and commentaries. The new volume presents four of Ford’s non-collaborative plays. Vickers writes an eleven-page introduction to the volume, “I have used the privilege of a general editor with the overview of the contents of this volume to pick out some of the features they share” (xxvii) but spends more pages presenting the case that ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore should be dated much earlier than previously thought, 1617-18, and that this is Ford’s first solely authored play.

The edition has pretty much everything I want; lengthy introductions to each play cover much of what is known, glosses are on the bottom of each page, and a helpful commentary follows each play. These old-spelling texts are edited anew from surviving quartos, collated, and presented in the order that Vickers believes the plays were written. Remember that for later.

Unusually, ‘Tis Pity is introduced by Vickers with the text, glosses, and commentary edited and compiled by Katsuhiko Nogami. Vickers does not explain the reason he wrote this introduction, but he presents a controversial interpretation, arguing that while Giovanni may be the protagonist he is not the play’s hero for Ford presents the character “at his own self-estimate, setting himself against society” and its values. As the play develops, Giovanni becomes increasingly “self-indulgent until he puts himself outside of all shared norms of human behavior” (12). This interpretation must be important to Vickers; he devotes 27 of the introduction’s 42 pages to it. The text, like all texts in this edition, is beautifully edited.

Tom Cain writes in his introduction to The Lover’s Melancholy “on balance, the evidence marginally supports the view that this was the first play Ford wrote on his own” (209). It is commendable that Vickers let this stand. Ford acknowledged his debt to two sources, Famiano Strada’s poem Prolusiones academicae and Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, which, Cain writes, “of these, the debt to Burton is far the greatest.” He devotes fifteen pages to these and other sources, two to the political context and two more to a stage history, but the bulk of his introduction explores what Cain believes are the strengths and flaws of the play, flaws Cain attributes to Ford’s relative inexperience as a non-collaborative playwright.

Sources for The Broken Heart are a vexing problem, but editor Lisa Hopkins works through these carefully in her introduction. She also makes a “reasonable guess” for a date of c. 1629-30 (415). In her estimation, this play, despite the seeming coldness of its characters, “seethes with emotion” (425), because “these characters do have hearts that feel, and indeed break; they just don’t talk about it” (426). Multiple reasons are given for this paradox.

Eleanor Lowe and former “Talking Books” guest Martin Wiggins edited what I am told is the first scholarly edition of The Queen, or the Excellency of her Sex. Their introduction is sensitive to ways that language is used to manipulate the politics of the story and its strife over gender and royal power. I had not read the play before and found this very helpful. Lowe and Wiggins include a detailed publication history. I hope we do not have to wait so long for volume V of The Collected Works of John Ford.

What Was Shakespeare Really Like?, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

What Was Shakespeare Really Like?, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Want a Shakespeare book that is just plain fun? My current favorite is What Was Shakespeare Really Like? by Stanley Wells. This is not an academic book, one of the front cover endorsements is from Kenneth Branagh (“Brilliant”) and the forward is written by actor Stephen Fry, but the world needs popular books about Shakespeare and Wells, who has written a few, has given us another good one.

The book began as four lectures for the Shakespeare Centre, part of the Birthplace Trust campus in Stratford-upon-Avon, to celebrate Prof. Wells’s ninetieth birthday, but his talks moved online due to the pandemic and are now fleshed out a bit for print. The chapter titles ask four questions answered in each chapter.

“What Manner of Man Was He?” Wells points out that this is a paraphrase of a question asked by some Shakespearean characters in Henry IV, Part One, Twelfth Night, As You Like It, and The Winter’s Tale, and we may add two more, Antony and Cleopatra, though that inquiry is about crocodiles, and in Shakespeare’s portion of Henry VIII. It is smart to turn this typically Shakespearean line around and make it a query about the Bard himself.

Wells documents the opinions of Shakespeare’s contemporaries of him and the public records that reveal his work habits, finances, family, the knowledge revealed in his plays, and lots more. Wells does not speculate through any of this. Some matters, such as Shakespeare’s religion are interpreted from the facts, but Wells presents the facts then tells readers his interpretation, “If I had to express my own views I should say that he was a conforming Protestant, did not have Roman Catholic sympathies, and profoundly disliked the Puritans’ (25).

“How Did Shakespeare Write a Play?” makes the sensible assertion that the choice of subject was determined by Shakespeare with the other sharers of his company and that Shakespeare’s work schedule was arranged to accommodate a workload of approximately two plays a year. Wells addresses plotting / adaptation, dramatic forms, compositional habits, and the mechanics of staging Shakespeare’s texts.

Chapter 3,“What do the Sonnets Tell Us About the Author?” is even handed in explaining the content of the 1609 edition but Wells is less even handed answering the question. He gives the case for a non-autobiographical interpretation of the sonnets in a few sentences. His autobiographical interpretation lasts many pages, making the presentation lopsided. Wells is probably safe in doing this, most of my friends believe many sonnets are autobiographical, but as a skeptic I see problems with both sides. Other sonnet sequences are non-autobiographical love stories, but simply writing about different subjects does not justify implying Shakespeare’s sonnets are autobiographical. They may or may not be. Wells also makes the point that two of the sonnets, 138 and 144, if autobiographical, are embarrassing to Shakespeare, and this is one reason Wells does not believe Shakespeare saw the book through the press but shared these poems exclusively with friends. I wonder why Shakespeare would embarrass himself to his friends if those sonnets are autobiographical, as Wells believes? Certainly, there are at least some autobiographical sonnets, 136, which puns on Shakespeare’s name, and 145 which is about Anne Shakespeare, nee Hathaway, plus a few others that interact with these, but that does not mean that two of the sequences, sonnets 1-17 and 78-86, or all the sonnets in the 127-52 sequence are necessarily autobiographical. I have never heard an argument that proves or disproves the autobiographical content of these sequences. It is a matter of faith. Perhaps someday, if a compelling negative argument is made or new negative evidence found, we will regard those who find Shakespeare’s life in these sequences as quaint as the old scholars who believed that Prospero’s “Our revels now are ended” speech (The Tempest, 4.1.148-58) was Shakespeare’s farewell to the theater. I have a very large quibble with this chapter, but it is still a quibble.

In the final chapter, “What made Shakespeare Laugh?” Wells cautions that Shakespeare may well have included humorous bits that he knew would make audiences laugh but do not reflect his sense of humor, then goes on to point out the kinds of humor Shakespeare used such as puns and other wordplay, described slapstick, embarrassment, and scenes deflating pomposity. Wells nods to the humor in Venus and Adonis, the sonnets, and Hamlet. The part I found most interesting is the parsing of Shakespeare’s comedies by their humorous styles, the first phase being plays up to about 1600, Two Gentlemen of Verona through A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which Welles calls Shakespeare’s happiest comedies. The next group are The Merchant of Venice through As You Like It, plays with a comic antagonist, a character type missing from the first group. The final group looks at the latter comedies, from Measure for Measure through The Tempest, concerned with moral matters where comedy is used to explore that morality or change the serious tone.

Wells ends with what is probably the most complete autobiography he will write. He concentrates on his Shakespeare interactions from first exposure as a pre-teen to his many successes over several decades leading in his knighthood in 2016. More projects and books followed including, of course, What was Shakespeare Really Like? Though the first four chapters are not a formal Shakespeare biography, the book can be recommended to those who want a biography. Except, possibly, for that third chapter, Wells sticks to facts far better than most biographers. Stanley Wells was my first “Talking Books” guest and taught me much about how to develop the column. I am very grateful.

Shakespeare, Malone and the Problems of Chronology, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Shakespeare, Malone and the Problems of Chronology, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Whenever Tiffany Stern sees a house of cards, she pulls a card from the bottom and lets it all fall. Her latest target is the scholarship attempting to establish the chronology of Shakespeare’s plays. She brilliantly demolishes that house.

Edmond Malone wanted to discover both the order Shakespeare’s plays were written and the year he wrote them, and so originated the systematic study of that chronology in An Attempt to Ascertain the Order in Which the Plays Attributed to Shakespeare Were Written in 1778, revised in 1790, then revised again and published posthumously in 1821. After Malone, successive generations of Shakespeare scholars have revised the conclusions of Malone and those who followed by considering new evidence or rethinking old evidence. They do what Malone did, do it a bit better, but repeat some of his mistakes.

One kind of chronological evidence is external to the plays, such as court records, the Stationers’s Register, Philip Henslowe’s so-called Diary, Robert Greene’s Groats-Worth of Wit, and Francis Meres’s Palladis Tamia. These can, at best, establish that Shakespeare’s plays existed in some form when they are mentioned in these documents and books, though the titles may sometimes refer to similar plays by other playwrights. Stern explores Malone’s many mistakes when examining external evidence.

Internal evidence takes many forms. One is Shakespeare’s source texts such as Holinshed’s Chronicles and North’s translation of Plutarch. Shakespeare’s plays could not have been written before the publication of his sources. Another is verbal parallels. Scholars relying on these sometime make mistakes for we do not always know if Shakespeare influenced other writers or was influenced by those writers so using the publication dates of the parallel texts can be misleading. Malone used stylometric studies to date plays centuries before that word was invented. Another problem: those who wish to date the plays may use wishful thinking when identifying contemporary references. I am bothered by dating Romeo and Juliet by the reference to the earthquake in 1.3.25, one of several references to the past that helps the Nurse ascertain Juliet’s age. Those other references are fictional, so why do scholars single out the Dover Straits earthquake of 1580 as being Shakespeare’s inspiration when that quake was not located in Italy but in the English Channel? Shakespeare may have had that earthquake in mind but he knew that that Italy was prone to earthquakes, there are references to earthquakes in Julius Caesar and Much Ado About Nothing which takes place in nearby Sicily, and so included that for local color. The connection is too tenuous to use to date the play. Malone too was prone to connecting lines in Shakespeare’s plays to real events Shakespeare may not have had in mind. Stern considers these and other kinds of internal evidence then supports Samual Schoenbaum conclusion that “internal evidence can only support hypotheses or corroborate external evidence” (39).

Malone did not meaningfully engage with Shakespeare’s revisions or revisions by others of Shakespeare’s texts. An example of the latter are the act divisions added to some quarto plays for publication in the First Folio; these divisions indicate when to trim the candle wicks after plays were moved to the Blackfriars Playhouse. We now know that music was also added for Blackfriars performances, and it is here that Stern demolishes the claim that Thomas Middleton revised Macbeth by showing that the songs and dances from The Witch were added by either John Wilson or Robert Johnson, depending on the date of the additions. This makes much more sense than positing revision based on samples of text too small to yield reliable stylometric results. Stern also examines other kinds of late additions, such as masques, epilogues, and stage directions. Taken together, these suggest the need for a range of dates because the texts we have are seldom if ever the play that came off Shakespeare’s quill. “The very idea that a play has a date, rather than a range of dates, and a moment of completion, rather than – with revision and revival – several, is challenging” (59).

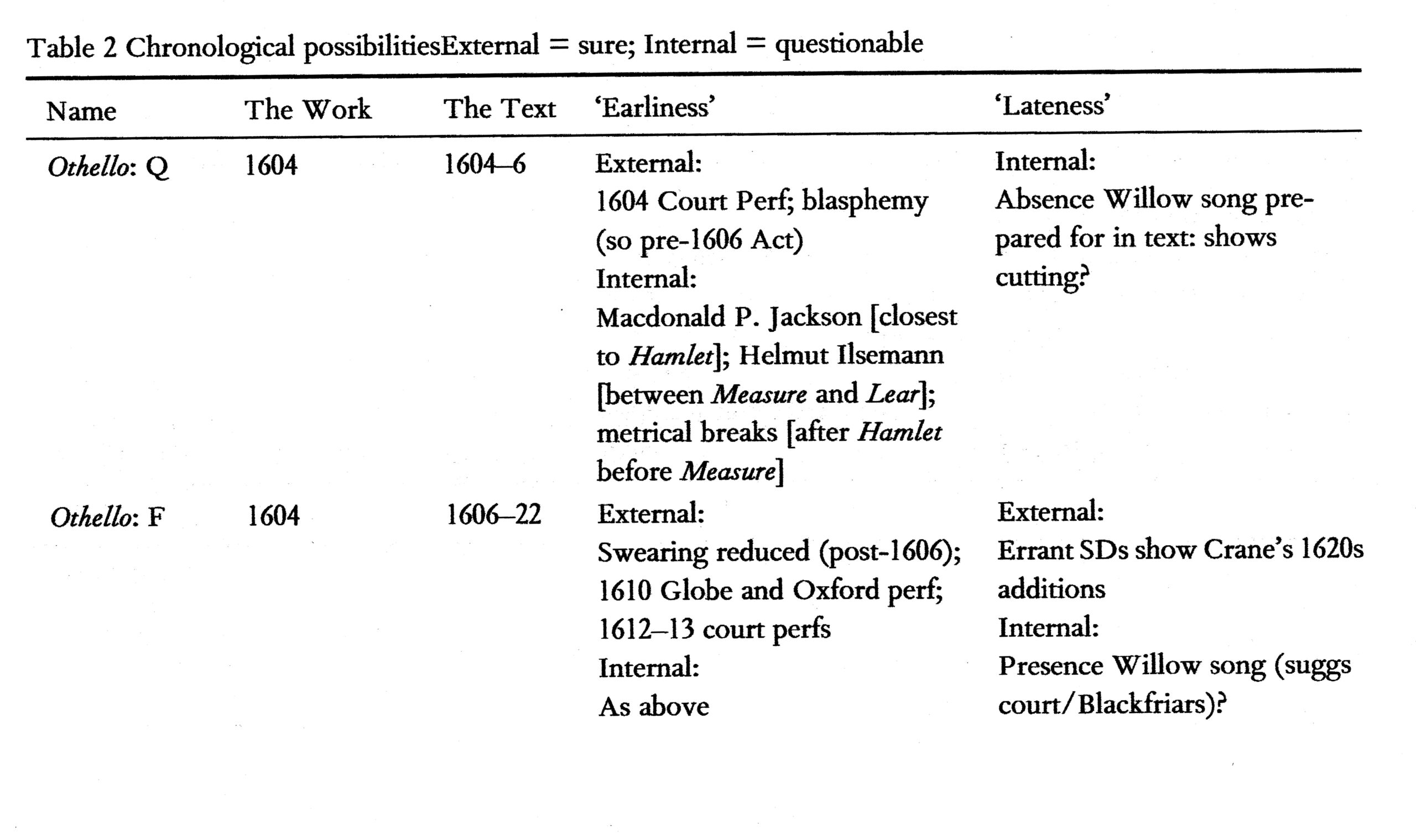

Shakespeare’s plays as we have them defy a single date of completion, yet scholars still try to identify one. The penultimate chapter looks at some failures by colleagues trapped in Malone’s framework with a couple of other examples of some who have begun to consider date ranges. That leaves the question of what a date range will be like. The book concludes with two answers to that question which take form of tables. The Othello table is included here for it is easier to show than to explain.

Othello is a tricky play because there are both quarto and folio versions and these greatly differ. Stern shows in this table how to make the date ranges of both versions visually and logically clear.

What would Stern make of Stanley Wells’s three date-based types of Shakespearean comedies, such as the first group from approximately 1590-1600? (Wells asserts dates generally but does specify years for the remaining groups.) I suspect that Stern would suggest corrections about the way the dates are discussed along the lines of her tables, but with those qualifications would probably accept the dates as generalizations in the way she accepts that 1604 is a reasonable date for the original composition of Othello. Certainly, Wells identifying the three approaches to comedy is valid and the plays seem to cluster early, middle, and late in Shakespeare’s career. What about ordering the plays by date in Ford Volume IV? Stern questions if the publication of complete or collected works should be by the order plays were written since this knowledge can be so faulty and points out that the First Folio orders the plays by genre, and even within genres does not order the plays chronologically, though she does not specifically answer my question. Stern is arguing that we should be far more agnostic about settling for a single date and both more flexible in approach and rigorous in thought when we try to understand chronology. This little book has a lot to say about current scholarly approaches to chronology.

Shakespeare Survey 75, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Shakespeare Survey 75, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

I include this annual because it is edited by former guest Emma Smith and I spotlight the articles that made great impressions on me. The theme in this volume is Othello, though several non-theme articles and reviews are also published.

I especially want to spotlight Andrea Smith‘s “‘More Fair Than Black:’ Othellos on British Radio” for breaking new ground in Shakespeare performance scholarship. Smith does more than survey Othello broadcasts but also looks at the matter of racial casting, note the article’s title, and is illuminating on the world that preferred certain types of actors and performances during 88 years of Othello broadcasts. The article is excellent on these broadcasts and the audio equivalent of blackface.

Iman Sheeha explains Barbary, who is said to have a song of “Willow” in the Folio text of Othello in “’A Maid Called Barbary’: Othello, Moorish Maidservants, and the Black Presence in Early Modern England.” The author starts and ends there, but readers are taken on a fascinating tour through the relationships of serving women and the women they serve as surveyed in several early modern plays. Like Emilia to Desdemona, they tend to be older, bawdy, and adventuresome. I will add the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet to Sheeha’s list. From there she considers black servants in early modern literature, actual black servants in early modern England and the abuse often made of them by their masters. They are in contrast to Barbary who breaks with the naughty servant type, having an innocence like Desdemona’s. I learned much that will inform future readings of early modern texts.

John-Mark Philo contributes “Ben Jonson’s Sejanus and Shakespeare’s Othello: Two Plays Performed by the King’s Men in 1603,” an exploration of the connectiveness of Shakespeare and Jonson with Shakespeare acting in at least of two of Jonson’s plays, the production of five of Jonson’s plays by the King’s Men, the possibly that Shakespeare’s was the co-author in the lost original Sejanus, that their plays were given in tandem in a great house and a university town, and several other connections. Scholars have not previously paired Sejanus and Othello in the ways Philo does, but he finds thematic commonalities in manipulation, jealousy, gulling, and references to medicine, poison, and practice.

We now move to the not thematic essays starting with “Warning the Stage: Shakespeare’s Mid-Scene Entrance Conventions.” This study began when Margaret Jane Kidnie noticed that Osric arrives in different contexts in Hamlet Q2 and F. In Q2 he interrupts a private conversation, but Horatio sees him coming in F and warns Hamlet of the pending intrusion. Kidnie wonders how early modern actors handled these situations and so Kidnie read prodigious amounts of scholarly literature and studied the mid-scene entrances in twenty-six plays, including eighteen playhouse manuscripts, to determine how such arrivals were written. She finds four different kinds of mid-scene entrances when there is warning of the character approaching and four more types when these characters arrive without warning. The remainder of the article applies these findings to several different plays then circles back to Hamlet.

In my personal library is a book that once belonged to the early modern scholar C. L. Barber, Suffering and Evil in the Plays of Christopher Marlowe by Douglas Cole. The book is lightly annotated with some underlining, arrows, a couple of questions written in the margins, and several brief notes. It is a privilege to think along with one of the twentieth century’s great critics as I read Cole’s book over his shoulder. Richard Ashby has the privilege of thinking along with the influential director and critic Harley Granville-Barker as he reads the marginalia in both copies of Granville-Barker’s Arden 1 edition of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus in “’But When Extremities Speak’ – Harley Granville-Barker, Coriolanus, the World Wars and the State of Exception.” Ashby permits us to read these notes over his shoulder.

Granville-Barker wrote about that play, but his marginalia go far beyond his Preface prefiguring current research about Shakespeare and war. Barker lived in New York during the early years of World War II working for the British Information Service, tasked with moving America into joining the war with the allies. In an undated comment about the Volscian plot to sneak attack Rome, 1.2.22-5, Granville-Barker wrote simply, “Pearl Harbor,” referring to the sneak attack that brought the United States into the war when its Pacific fleet was attacked on 7 December 1941. His annotations are informed by twentieth century debates about appeasement and suspending democracy during a state of emergency. Ashby could not have known this when he wrote his article, but the forthcoming (as I write this) American election on 5 November 2024 may end with a former president resuming power, a man who tried to overturn a democratic election in 2021 and has spoken of suspending the Constitution, making Ashby’s over the shoulder read especially timely.

The annual reviews are back to normal with the ending of the Covid closures, so former guest Lois Potter covers London productions with her usual grace and good sense. Peter Kirwan reviews shows outside of London including reaching back for some pre-reopening productions, such as the Royal Shakespeare Company streaming Henry VI, Part One. After missing 74, the retiring Russell Jackson returns with his last reviews of books on Shakespeare in performance. All five book and performance reviewers do great work. I shall stop my survey of Shakespeare Survey 75 here except to note that this very strong issue will reward your time.

On a concluding note, my friend Alden T. Vaughan passed away in March 2024. I sneak him in the “Update” because he was happily married to and a collaborator of former “Talking Books” guest Virginia Mason Vaughan, so their books together were discussed when I interviewed Ginger, as she is known to friends. Alden was a scholar of Colonial America with a special interest in race. In fact, I have been trying to find his book Roots of American Racism: Essays on the Colonial Experience for some time. Alden’s career was mostly at Columbia University where he is emeritus. Alden transitioned to first-rate Shakespeare work with and without Ginger in the books they wrote and edited together, curating a Folger show called “Shakespeare in America,” and in journal articles. To know Alden is to miss him and mourn the loss of a genuinely good man with such a knowledgeable and incisive mind.

Bibliography

Burton, Robert. Anatomy of Melancholy. Oxford, 1621.

Cole, Douglas, Suffering and Evil in the Plays of Christopher Marlowe. Princeton University Press, 1962.

Donovan, Kevin J. King Lear, Shakespeare: The Critical Tradition. Arden Shakespeare, 2023.

Granville-Barker, Harley, Prefaces to Shakespeare: Volume II. Princeton University Press, 1947.

Greene, Robert. Greenes, Groats-Worth of Witte, bought with a million of repentance. London, 1592.

Goy-Blanquet, From the Domesday Book to Shakespeare’s Globe: The Legal and Political Heritage of Elizabethan Drama. Brepols Publishers n. v., 2023.

Holinshed, Raphael. The Chronicles of England. London, 1577, revised 1587.

Meres, Francis. Palladis Tamia, Wits Treasury. London, 1598.

North, Thomas. The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans Compared. London, 1579, revised 1595, 1603.

Smith, Emma, ed. Shakespeare Survey 75. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Stern, Tiffany. Malone, Shakespeare and the Problems of Chronology. Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Strada, Famiano. Prolusiones academicae. Rome, 1617.

Vaughan, Alden T., The Roots of American Racism: Essays on the Colonial Experience. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Wells, Stanley, What Was Shakespeare Really Like? Cambridge University Press, 2023.