Talking Books – 69.1

Talking Books with Mark Thornton Burnett

I was first impressed by Mark Thornton Burnett in 1999 when he was on a Shakespeare Association of America panel in San Francisco. His thrilling talk “Constructing ‘Monsters’ on the Shakespearean Stage” was corrective. I knew that the words “monster” and “monstrous” appeared in Shakespeare, but my understanding was tainted by the old Universal films featuring the Wolf Man, Dracula, and other movie monsters. Prof. Burnett introduced the physical abnormalities, real and perceived, that were called monstrous in early modern times. This talk was incorporated into Constructing ‘Monsters’ in Shakespearean Drama and Early Modern Culture, published by Palgrave in 2002. It begins with places the early modern English would go to see so-called monsters, then looks at the monstrous in Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, three of Shakespeare’s plays – Richard III is himself considered monstrous – and ends with Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair. I was not then aware of Burnett’s previous books.

I was first impressed by Mark Thornton Burnett in 1999 when he was on a Shakespeare Association of America panel in San Francisco. His thrilling talk “Constructing ‘Monsters’ on the Shakespearean Stage” was corrective. I knew that the words “monster” and “monstrous” appeared in Shakespeare, but my understanding was tainted by the old Universal films featuring the Wolf Man, Dracula, and other movie monsters. Prof. Burnett introduced the physical abnormalities, real and perceived, that were called monstrous in early modern times. This talk was incorporated into Constructing ‘Monsters’ in Shakespearean Drama and Early Modern Culture, published by Palgrave in 2002. It begins with places the early modern English would go to see so-called monsters, then looks at the monstrous in Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, three of Shakespeare’s plays – Richard III is himself considered monstrous – and ends with Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair. I was not then aware of Burnett’s previous books.

Masters and Servants in English Renaissance Drama and Culture: Authority and Obedience was published by Palgrave five years earlier. Burnett takes a New Historicist and Cultural Materialist look at the anxiety of masters and servants as social forces destabilize their relationship. Anxiety is an important theme in some of Burnett’s work. Look for that word again in this introduction.

Burnett has edited several books. The earliest of these is New Essays on ‘Hamlet,’ co-edited with John Manning for AMS Press in 1994. The essays use several early modern discourses to contextualize the play, in addition to some modern approaches. There are a couple of notable contributors, Lisa Hopkins and former “Talking Books” guest Martin Wiggins. Burnett’s chapter looks at the “discourses of secrecy circulating in the English Renaissance” to better understand a play that is in part about anxiety that the old order will end (23).

Burnett did not contribute a chapter to Shakespeare and Ireland: History, Politics, Culture, a book he edited with Ramona Wray for Palgrave in 1997. I usually skip such books, but it gives me the opportunity to explore an area new to “Talking Books,” so see the questions below.

The Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and the Arts, edited with Adrian Streete and Wray for Edinburgh University Press in 2011, also has an impressive list of contributors: Sonia Massai, Alexa Alice Joubin, Kate Rumbold, the late David Bevington, Fran Teague, Andrew James Hartley, Judith Buchanan, and Susanne Greenhalgh, amongst them. Burnett’s chapter, “Shakespeare Exhibition and Festival Culture,” goes back to the Jubilee in 1769 to understand what he identifies as a nationalistic impulse to make a pilgrimage, celebrate Shakespeare, and spend money at Stratford-upon-Avon’s institutions. I want to thank the editors for asking me to update my three-part history of Shakespeare comic books published in SN back in 2006-7. There was a lot of new material to describe, and I am grateful for the opportunity to extend that history as a chapter in The Edinburgh Companion.

Reconceiving the Renaissance was co-edited with Ewan Fernie, Clare McManus, and Wray for Oxford University Press in 2005. The book charts ways that theory has changed critical ideas in textuality, identities, materiality, and values. Burnett edited the appropriation chapter and co-edited the chapter on histories with Wray. It is good at explaining and excerpting articles that show what theory has done in these areas, but it makes me queasy, which I will explain in the “Talking Books Update.”

Burnett is probably best known for two decades of work on screen Shakespeare with three authored books, two more co-edited with Wray, another co-edited with Streete, another edited by himself, plus chapters in books edited by others. One of his chapters in a book edited by others is “Gendered Play and Regional Dialogue in Nanjundi Kalyana” in Shakespeare and Indian Cinemas: “Local Habitations,” edited by Poonam Trivedi and Paromita Chakravarti for Routledge in 2018, and as usual, Routledge ignored my request for a review copy so I cannot describe his chapter here. I will ask Burnett to tell us about the chapter in the interview.

Shakespeare, Film, Fin de Siècle was edited with Wray for Macmillan, and released, you guessed it, in 2000. The dust jacket informs readers that the essays “argue that cinematic interpretations of Shakespeare are key instruments with which western culture confronts the anxieties attendant upon the transition from one century to another.” There is that word again. The films discussed imagine our own concerns as Shakespeare’s. This has been said of many stage and screen productions, but the contributors find ways to apply this basic claim to the change of millennia, and Shakespeare lived through one of those. The impressive cast of writers include Judith Buchanan again, Stephen M. Buhler, Margaret Jane Kidnie, Emma Smith, and Burnett himself who writes about Adrian Noble’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1996) by using the character of the Boy to interpret the film and the story. He also teams with Wray to interview Kenneth Branagh.

Shakespeare, Film, Fin de Siècle was edited with Wray for Macmillan, and released, you guessed it, in 2000. The dust jacket informs readers that the essays “argue that cinematic interpretations of Shakespeare are key instruments with which western culture confronts the anxieties attendant upon the transition from one century to another.” There is that word again. The films discussed imagine our own concerns as Shakespeare’s. This has been said of many stage and screen productions, but the contributors find ways to apply this basic claim to the change of millennia, and Shakespeare lived through one of those. The impressive cast of writers include Judith Buchanan again, Stephen M. Buhler, Margaret Jane Kidnie, Emma Smith, and Burnett himself who writes about Adrian Noble’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1996) by using the character of the Boy to interpret the film and the story. He also teams with Wray to interview Kenneth Branagh.

Screening Shakespeare in the Twenty-First Century was edited with Wray for Edinburgh University Press in 2006. The book picks up where Fin de Siècle left off, looking at the ways modern filmmakers appropriate or change Shakespeare’s concerns into ours in adaptations, spin-offs, and a documentary series. The starry cast includes Susanne Greenhalgh again, this time in collaboration with Robert Shaughnessy in a must-read chapter that looks at matters of race in televised Shakespeare. Other contributors are Richard Dutton, Sarah Hatchuel, Courtney Lehmann, and former “Talking Books” guest Samuel Crowl. Burnett writes about the Hamlet films of Campbell Scott/Eric Simonson, Michael Almereyda, and Stephen Cavanagh. The chapter examines incidents of surveillance in these films to comment on seeing Shakespeare and the past while addressing anxieties about memory and authenticity.

Although he did not write a chapter for Palgrave’s 2011 book Filming and Performing Renaissance History, 2011, Burnett edited the book with Streete. It is about screen and live performance of early modern texts and history. There is a bit of Shakespeare. I was especially impressed by Jesús Tronch Pérez’s chapter on Spanish-language Shakespeare film biographies that question Shakespeare’s status in modern culture, Christie Carson’s look at Henry V on the modern Globe stage, and Andrew Higson on what the editors call “the heritage film industry,” which argues that viewers can feel they are watching high art when they are really consuming something quite middlebrow under a classic polish. The introduction is also valuable for questioning one aspect of presentism on pp. 6-8, though there is no mention of the problem I find with presentism: its disinterest in hermeneutics.

Great Shakespeareans Volume XVII: Welles, Kurosawa, Kozintsev, Zeffirelli is part of the series General Edited by Peter Holland and Adrian Poole. It was published by Bloomsbury in 2013. This volume was co-authored with Marguerite Rippy, Lehmann, and Wray. Burnett wrote the introduction and contributed the insightful chapter on Akira Kurosawa. He in part notes Kurosawa’s visual and humanist qualities and the success the filmmaker had relocating Shakespeare in a Japanese milieu, a success that inspired many other Asian stage and film directors of Shakespeare.

The first of Burnett’s authored movie books is Filming Shakespeare in the Global Marketplace, published by Palgrave in 2007. The basic topic is Shakespeare as a commodity distributed globally, but that commodity is looked at through various windows such as race and ethnicity, memory, spirituality, and the Holocaust. Anxieties about “fresh forms of electronic imperialism” are expressed (1). Most of the adaptations and spin-offs discussed are English language films, though not all. Get the paperback with Burnett’s preface describing ways that the global presence of Shakespeare films has changed in the five years since the hardcover was published.

This brings us to the excellent Shakespeare and World Cinema from Cambridge University Press in 2012. The book exposes us to seventy-three non-English language Shakespeare films from Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and even France, films that have been largely overlooked in previous discourses. Burnett uses three approaches, each applied according to the content of the films discussed: auteur theory, commonalities and differences of films made in Latin America and Asia, and varied approaches to reculturing Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet. The idea is, in part, to test “the advantages and disadvantages of particular approaches” (9) in addition to viewing some of the same films from these different vantages. If you only know the Shakespeare films available on DVD in English or with English subtitles, then most of these films will be new to you.

This brings us to the excellent Shakespeare and World Cinema from Cambridge University Press in 2012. The book exposes us to seventy-three non-English language Shakespeare films from Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and even France, films that have been largely overlooked in previous discourses. Burnett uses three approaches, each applied according to the content of the films discussed: auteur theory, commonalities and differences of films made in Latin America and Asia, and varied approaches to reculturing Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet. The idea is, in part, to test “the advantages and disadvantages of particular approaches” (9) in addition to viewing some of the same films from these different vantages. If you only know the Shakespeare films available on DVD in English or with English subtitles, then most of these films will be new to you.

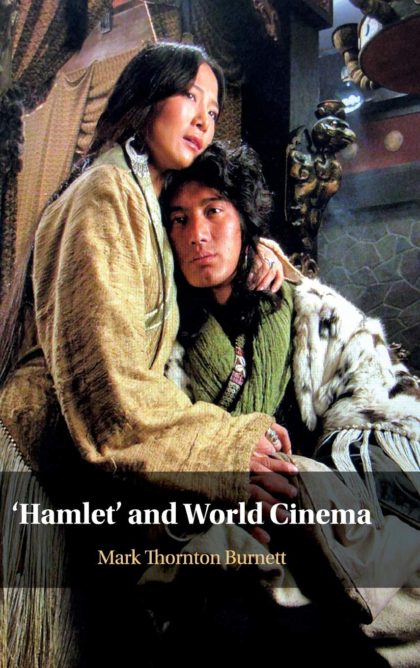

I like ‘Hamlet’ and World Cinema even more. The 2019 Cambridge University Press book looks at appropriations of Hamlet in Western Europe, Africa, Brazil, China and Japan, India, Turkey and Iran together, and finally, Russia and Eastern Europe. Burnett therefore includes some fairly straight adaptations of Hamlet; Grigori Kozintsev’s Gamlet receives more than a dozen pages. For each film, Burnett takes us through the process of finding a setting in the director’s culture that makes sense of the story and the characters. He takes care to understand the issues addressed by making that film at the time it was made. The vast majority of these films are new to me, and probably to you. Burnett interviewed the filmmakers when he could, bringing us the films from their perspectives. We are privileged to join the author on this journey.

Mark Thornton Burnett is Professor of Renaissance Studies at Queen’s University, Belfast; Member of the Royal Irish Academy; Fellow of the English Association; Trustee and Director of the British Shakespeare Association; and Director of the Sir Kenneth Branagh Archive located at Queen’s University, Belfast, and General Editor of the Bloomsbury series “Shakespeare and Adaptation.” He is currently PI of the “Indian Shakespeares” project at Queen’s, which examines Shakespeare’s manifold Indian habitations. Thus far, as part of the project, there have been screenings, an exhibition, and a conference.

MPJ: The subjects of your books are unusually diverse, which makes me curious. Did any books or authors put you on the path to your career?

MTB: At a formative time, when I was starting graduate work, the books of Shakespeare critic Emrys Jones and historian Sir Keith Thomas, particularly Religion and Decline of Magic, put me on a path. Thomas’s work has a density and anecdotal energy, as well as a social historical orientation, that I really admire. Jones and Thomas supervised my PhD. Theoretically, I took inspiration at an early stage from Stephen Greenblatt’s Renaissance Self-Fashioning and Alan Sinfield and Jonathan Dollimore’s collection, Political Shakespeare. Renaissance Self-Fashioning I liked for its interpretive fluidity and material emphases; Political Shakespeare I warmed to for its radical, demythologizing approach.

MPJ: Whose books do you greatly admire?

MTB: I would mention anything by the above and the social history books written by my father, John Burnett, which really got me interested in history from below or from the margins: both Useful Toil and Destiny Obscure are great reads! The discussion of autobiographical work by ordinary people was unprecedented for its time. I have learned a huge amount from books by Pascale Aebischer, Thomas Cartelli, Samuel Crowl (his Shakespeare at the Cineplex is the first book to explore Kenneth Branagh’s work in detail), Russell Jackson, Alexa Alice Joubin (her Chinese Shakespeares innovatively extends geographies and cultures), Dennis Kennedy, Douglas Lanier, Courtney Lehmann (her Shakespeare Remains brilliantly combines analyses of early modern and postmodern worlds), Katherine Rowe, Jyotsna Singh, Lisa Starks, and Poonam Trivedi.

MPJ: Specific works by all these writers will be listed in the bibliography. Masters and Servants in English Renaissance Drama and Culture does our profession a great service, pun not really intended. It is interesting that the early modern economy was so dependent on the serving/apprentice class. What don’t most of us understand about this today?

MPJ: Specific works by all these writers will be listed in the bibliography. Masters and Servants in English Renaissance Drama and Culture does our profession a great service, pun not really intended. It is interesting that the early modern economy was so dependent on the serving/apprentice class. What don’t most of us understand about this today?

MTB: The fact that there was a whole institution there; that servants formed part of the household; that apprenticeships were a vital part of the economy. And that this had its literary counterpart in the drama of the period.

MPJ: Do you mean that boy actors were apprenticed to older actors through one of the guilds?

MTB: This was part of it, but actors as apprentices was only one aspect of the institution. Apprentices were found in all the major trades and professions.

MPJ: You read widely in the writing of the era including letters, court records, diaries, books written for a servant readership, and take in-depth looks at Jack of Newbury (Thomas Deloney), which is prose fiction and a book I must read, and the plays The Changeling (Thomas Middleton and William Rowley), The Duchess of Malfi (John Webster), King Lear, Twelfth Night, and The Shoemaker’s Holiday (Thomas Dekker). Could you have chosen other plays, such as Ben Jonson’s Volpone and The Alchemist, or The Comedy of Errors?

MTB: Yes, by all means. Volpone offers a particularly nuanced vision of the master-servant relationship in the actions and plotting of Volpone and Mosca (more parasitic than economically institutional), while The Comedy of Errors is fascinating for the ways in which it transplants the Roman institution of slavery into an Elizabethan institution of service, complete with contemporary echoes.

MPJ: Is there any other prose fiction of interest?

MTB: I really like Henry Chettle’s Piers Plainness: Seven Years’ Prenticeship, not least because of its concern with social mobility, its references to Elizabeth I, its mediation of apprentice discontent and its engagement with contemporary youth culture.

MPJ: Which books by our contemporaries were informative?

MTB: Domination and the Arts of Resistance by James C. Scott, which gave me a theoretical take on the subject, and Faultlines by Alan Sinfield, which gave me a steer on group protest. I also gained immeasurably from the gendered discussions by critics and historians, Patricia Crawford and Sara Mendelson, Frances Dolan, Margaret W. Ferguson, and Mary Prior.

MPJ: I have noticed books on the subject published since yours.

MTB: There are so many studies now! David Evett’s Discourses of Service in Shakespeare’s England is wonderfully attentive to the linguistic and poetic aspects of representations; Michael Neill in Putting History to the Question is typically eloquent and incisive; David Schalkwyk’s Shakespeare, Love and Service is so sensitively attuned to the ethical and emotive aspects of the institution.

MPJ: Most of your chapters in Constructing “Monsters” are about different plays, but the first explores sites where the people then called monsters were seen, such as fairgrounds and taverns. I suppose one equivalent is the modern side show at a carnival and another is the Tod Browning movie Freaks (1932). You also point out that early modern writings about the people displayed was itself a kind of exploitation. I do not think your book is that. I wonder, though, if there is a modern equivalent to such writings?

MPJ: Most of your chapters in Constructing “Monsters” are about different plays, but the first explores sites where the people then called monsters were seen, such as fairgrounds and taverns. I suppose one equivalent is the modern side show at a carnival and another is the Tod Browning movie Freaks (1932). You also point out that early modern writings about the people displayed was itself a kind of exploitation. I do not think your book is that. I wonder, though, if there is a modern equivalent to such writings?

MTB: There certainly are modern equivalents, yes. I consulted some of them and their nineteenth-century equivalents. Such works aside, I found most useful in that book archival and theoretically informed studies and here I would mention Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s edited collection, Monster Theory: Reading Culture, which is really applicable to early modern contexts, Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park’s book, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750, in which the illustrations are vital parts of the argument, and the path-breaking work of Rosemarie Garland Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies. This latter worked for me as a stimulating discussion of disability that could be applied to literary and cultural discussion.

MPJ: What other resources might scholars use?

MTB: If I were to go back to that study now, I would try and take far more advantage of digital access to online archives, particularly those of the record offices, and use to a greater extent new search facilities in EEBO. Those wonderful technical advances weren’t available to me then!

MPJ: You make different points with the five plays you study. Are there alternate plays you could have used to make the same points?

MTB: I might have looked at “monstrous” language and topoi in plays such as Coriolanus and ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore (John Ford) and there are no doubt other dramatic examples. The structure I used in the book worked, I like to think, without these other examples, as we have Shakespeare in the center framed by the curtains of Jonson and Marlowe!

MPJ: I was impressed by the book’s double table of contents in Reconceiving the Renaissance, one bare boned followed by an outline of the topics in each chapter. For your chapter on appropriation, you write a brief introduction, then print article excerpts that examine the relationship between the old artifacts as they have come down to us and appropriations of these artifacts, examine the politics of appropriation, and more. I was surprised to see an eight-page excerpt from Samuel Schoenbaum’s Shakespeare’s Lives in the appropriations chapter.

MPJ: I was impressed by the book’s double table of contents in Reconceiving the Renaissance, one bare boned followed by an outline of the topics in each chapter. For your chapter on appropriation, you write a brief introduction, then print article excerpts that examine the relationship between the old artifacts as they have come down to us and appropriations of these artifacts, examine the politics of appropriation, and more. I was surprised to see an eight-page excerpt from Samuel Schoenbaum’s Shakespeare’s Lives in the appropriations chapter.

MTB: We wanted to try and give a range of writings and authors who write about, and have written about, Shakespeare after Shakespeare, as it were. And, too, to suggest that “appropriation,” however it is defined, is not only about the screen, or cinema, or performance. Schoenbaum’s book fit right in there with that agenda (that is, it treats even biographical/critical works as objects of reinvention). It’s interesting to observe how frequently popular culture turns to, in order to reinvent, Shakespeare the man and Shakespeare the artist in representations that are increasingly the object of critical study. I’m thinking here of the recent stage production, The Upstart Crow, based on the television series.

MPJ: So much of your work is historically grounded that you seem a natural to introduce and edit this chapter with Dr. Wray. Not to read literary texts against historical texts is to invite all interpretations, however nonsensical, but don’t some people read just one interpretative idea into a literary text when there were competing ideas in early modern England?

MTB: Yes, I am sure they do, but what a historical approach enables is all manner of other approaches, which can cover economics, reception, politics, social considerations, and cultural practice. It’s fair to say that, in my more recent work on cinema, I’ve very much drawn on what I imbibed from new historicism and cultural materialism; indeed, I don’t think I could do what I do now without having had that grounding at an earlier stage.

MPJ: You must have excluded some readings in both the history and appropriation chapters solely for the reason of space.

MTB: Absolutely, and with great regret. There are numerous critics and extracts we all wanted to include. Hopefully, the suggested further reading section at the end of each chapter gives some guidance for the curious. For example, I am a great admirer of Lena Cowen Orlin’s Private Matters and Public Culture in Post-Reformation England, in part because of its tremendous marshalling of archival knowledge, and of Kate Chedgzoy’s Shakespeare’s Queer Children, because of its original gendered critique, but we weren’t able to include the extracts we wanted for reasons of space.

MPJ: Who practices theory on a very high level?

MTB: Well, it depends on how theory is defined. I very much admire scholars working in particular areas of early modern studies in which theory has made a difference; Ayanna Thompson on Shakespeare and race (the category of “wayward” is felicitously rolled out to encompass a great range of representations in her collection, with Scott L. Newstok, Weyward Macbeth), Dympna Callaghan on Shakespeare and feminist theory (I like how her A Feminist Companion to Shakespeare understands the field in terms of topics and approaches), Madhavi Menon on Shakespeare and queer theory (lots to dip into in her collection, Shakesqueer, which is intriguingly arranged according to plays), Jyotsna Singh on Shakespeare and postcolonial theory (her Shakespeare and Postcolonial Theory is so interculturally rich), Alexa Alice Joubin on Shakespeare and globalization (I still use her Shakespeare article, “Global Shakespeares as Methodology,” because it is about the “how” not the “what” of the field), Gabriel Egan on Shakespeare and editorial/textual theory (The Struggle for Shakespeare’s Text maps a history of editing in impressive detail), Juliet Fleming on Shakespeare and language/writing (her Graffiti and the Writing Arts of Early Modern England shows how you can do theory and social history side-by-side), and Douglas Bruster on Shakespeare and material culture (Drama and the Market in the Age of Shakespeare innovatively links the rise of drama, commerce and the economy) are names that spring immediately to mind. In the field of Shakespeare and film, Maurizio Calbi’s book, Spectral Shakespeare, is a really stimulating example of how deconstruction can be used to understand the work of adaptation.

MPJ: I have made many visits to Stratford-upon-Avon. At first, I did the tourist/Shakespeare properties thing, as you describe in your chapter in The Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and the Arts, but after a couple of visits, I returned because I liked the Teddy Bear Museum and Robert Vaughan Bookseller, both now gone, and the still there Chaucer Head Books, butterfly farm, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the river walks, and my favorite fish and chips shop, though the chips were sub-standard on my last visit. How do I conform to or defy your argument in that book, especially since I am a foreigner for whom Stratford is not a nationalistic impulse?

MTB: I think Stratford works multivalently, in national and international ways and both in between (that is, the national and international are mutually constitutive). I enjoy doing all the things you have mentioned and would add boating and charity shops!

MPJ: Boating! Others have their own takes on and address different issues about Stratford tourism. Whose has done good work here?

MTB: Barbara Hodgdon’s book The Shakespeare Trade must be the first port of call, so polemically persuasive in its interweaving of marketing and mythology. More recently, I have enjoyed an article by my colleague, Richard Schoch, “The Birth of Shakespeare’s Birthplace,” which is terrifically scholarly in how it maps the process whereby the birthplace came to be a place of pilgrimage, and also the collection edited by Katherine Scheil, Shakespeare and Stratford, which explores Shakespeare’s Stratford across time and space and in its fictional afterlives.

MPJ: We now turn to your anthologies, most of which were edited with other people. What are the advantages of collaboration?

MTB: The sense of a shared endeavor, the opportunity to learn from others, the benefits of being able to extend and deepen contacts from around the world. Above all, to join in a scholarly endeavor that brings intellectual rewards.

MPJ: What was the goal in publishing Shakespeare and Ireland?

MTB: At that time, attention was increasingly turning to how Shakespeare signifies in specific locations and cultures. We wanted to join that conversation. It must also be said that living and teaching in Northern Ireland had made me acutely aware of the legacies of Shakespeare in particular times and places, and I wanted to explore that further in relation to my own situation.

MPJ: The subject can break down into many topics, can’t it?

MTB: Absolutely, and there is more work being done in the area. Look out for the fantastic work on Shakespeare, Ireland and gender being conducted, for example, by Emer McHugh (University of Galway)! Her monograph, Irish Shakespeares: Gender, Sexuality, and Performance in the Twenty-First Century, is forthcoming from Routledge.

MPJ: Who else has done meaningful work in this subject?

MTB: There is a super collection edited by Janet Clare and Stephen O’Neill, Shakespeare and the Irish Writer, which looks not so much at Shakespeare and Ireland but the significances of Shakespeare to the Irish writer. And anything by Patrick Lonergan is a must on the subject: he has done very important work on the archives and history of Shakespeare performance in Ireland. I particularly admire his article, ‘“I found it out by the bogs’: Reviewing Shakespeare in Ireland,” in Shakespeare, and his chapter, “Shakespearean Productions at the Abbey Theatre, 1970-1985” (in Donald E. Morse, ed., Irish Theatre in Transition). Nor must one forget the pioneering studies of Andy Murphy: I particularly like his recent article, “Ireland, Ethnicity and the Nation: A Shakespearean Drama,” in Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, with its discussion of Shakespeare as Ireland’s national poet.

MPJ: Do you read film theory? Film history? Whose books have informed the way you think about film?

MTB: I look at both, or I try to as the literature is so voluminous. I try to read the national histories of cinema in whatever part of the world I am interested in, and, of course, that splits and fragments when you are exploring a country such as India which has multiple film industries in multiple languages. A textbook, and a very good one, I continually return to is David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson’s Film Art, rightly existing in multiple editions! I also read widely in world cinema theory.

MPJ: Tell us about the state of Shakespeare film books at the end of the twentieth century.

MTB: I think this was the moment where the discipline was expanding to include global Shakespeares, varieties of screen Shakespeares and other forms of mediatized Shakespeare. Very much part of that development was and is the series edited by Sarah Hatchuel, Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin, and sometimes Victoria Bladen, Shakespeare on Screen, published by Cambridge University Press, which continues to chart, alongside their conferences and seminars, new approaches to the field.

MPJ: I’ll mention that their books are organized around specific plays, so there are volumes about Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Othello, and The Tempest and the Late Romances. Victoria Bladen joined Hatchuel and Vienne-Guerrin for King Lear and Macbeth, and some volumes were published by Mont-Saint-Aignan Publications des Universités de Rouen et du Havre, pardon my French. I am not sure if you see your chapter in Screening Shakespeare in the Twenty-First Century as adjunct to your chapter in New Essays on “Hamlet,” but I do. The discourses of secrecy and the emphasis on surveillance in your chapters in these books complement each other.

MTB: That hadn’t occurred to me, but I can see your point now. I guess Hamlet has always been a play that has absorbed and fascinated me: I studied the play at school, was bowled over by Derek Jacobi as Hamlet which I saw as a teenager (ever since then, I’ve tried to catch the major Hamlet productions in some form or another) and was transfixed by Olivier’s film adaptation, which I first saw at college.

MPJ: I am the same about film and stage productions of that play. Who has written about other aspects of the Campbell Scott and Eric Simonson, Michael Almereyda, and Stephen Cavanagh Hamlet films?

MTB: Courtney Lehmann, Samuel Crowl and Peter Donaldson have written trenchantly and invigoratingly on Almereyda, and there is a plethora of fine work on the film in journals such as Literature/Film Quarterly, an important locus for studies in the field. On Hamlet in general, I do recommend the stimulating study by R. S. White, Avant-Garde Hamlet: Text, Stage, Screen, which has a brief but enlivening discussion of the Cavanagh film. It’s a shame the Scott/Simonson adaptation hasn’t been discussed more extensively, but Diana Henderson has a superlative discussion on the film as process in her fine collection, A Concise Companion to Shakespeare on Screen.

MPJ: I have the same question about Kurosawa’s Shakespeare films. There is a vast literature for his films.

MTB: There really is, no doubt because Kurosawa’s Shakespeare films were the first really to put world cinematic Shakespeares on the critical map. The books I’ve found most useful on Kurosawa are Stephen Prince, The Warrior’s Camera, which neatly divides Kurosawa’s career into four stages, and Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema, which adeptly alternates between Japanese self-images and western images. Right now, there is an increasing attention to issues of context, language and translation in Kurosawa: here, a trailblazer is the article by Jessica Chiba, “Lost and Found in Translation: Hybridity in Kurosawa’s Ran” in Shakespeare Bulletin.

MPJ: I have not been able to consult your chapter “Gendered Play and Regional Dialogue in Nanjundi Kalyana” because Routledge has ignored my review copy requests since at least 2013. What do you want us to know about that essay?

MTB: I wanted to stress in that chapter some of ways in which cinematic adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays in India assume localized significances that take energy from, even as they compete with, “Bollywood” Shakespeares, which are perhaps better known. But I also wanted to participate in the hugely important work being done by other critics on the subject of Indian Shakespeares, including the contributors to the book to which I contributed, Shakespeare and Indian Cinemas: “Local Habitations.” The editors of that book, Poonam Trivedi and Paromita Chavravarti, have inaugurated a magnificent project in introducing so many examples of Shakespeare on screen in India, from across so many languages and film industries.

MPJ: I found it difficult to summarize your concerns in Filming Shakespeare in the Global Marketplace in part because your discourse is so wide ranging as it follows both screen Shakespeare plays and spin-offs as they circulate around the world, and films made elsewhere appropriate Shakespeare to reflect on post-colonial lives. You certainly have convictions about all of this. What informed those convictions, and were books involved?

MPJ: I found it difficult to summarize your concerns in Filming Shakespeare in the Global Marketplace in part because your discourse is so wide ranging as it follows both screen Shakespeare plays and spin-offs as they circulate around the world, and films made elsewhere appropriate Shakespeare to reflect on post-colonial lives. You certainly have convictions about all of this. What informed those convictions, and were books involved?

MTB: I was trying in that book to use theories of globalization to account for and contextualise the phenomenon of Shakespeare and film/screen in its contemporary manifestations. The book that really got me going was Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large. I was most drawn to Appadurai’s concepts of “ideoscapes” and “global flows.”

MPJ: Will you please explain those a bit more?

MTB: “Ideoscapes” equates landscape with ideology: the theory works to highlight the ways in which particular geographies, and attitudes of mind, co-habit and interrelate. “Global flows” interlinks the flow of trade/capital and the flow of ideas.

MPJ: Thank you. Let’s assume people will read your new preface and get up to date as of 2012. What has happened since?

MTB: The preface to the paperback edition marked my own move to considering greater numbers of world cinema adaptations of Shakespeare, which I had tentatively begun to explore in the first edition of Filming Shakespeare in the Global Marketplace. In terms of what has come out recently, the three Shakespeare adaptations of Vishal Bhardwaj are vital (Maqbool/Macbeth, Omkara/Othello and Haider/Hamlet) as is a host of new releases from around the world. I try to keep up using the Learning on Screen website(http://bufvc.ac.uk/shakespeare), which continues to be updated and is a great place to start. Criticism and resources which take things much further than I did in Filming Shakespeare in the Global Marketplace include, but are not limited to, Andrew Dickson, Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys around Shakespeare’s Globe, a riveting travelogue and a trenchant account of global Shakespeares, the “MIT “Global Shakespeares” website (https://globalshakespeares.mit.edu), Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne Guerrin’s collection (one of many), Shakespeare on Screen: ‘Hamlet’, and Russell Jackson’s forthcoming collection with Cambridge University Press, The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Screen.

MPJ: Russell tells me this is a new book, not a third edition of his anthology Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Turning to Shakespeare and World Cinema, I am delighted that you prefer adaptation to appropriation for this book. I deplore the way that appropriation often replaces adaptation in our discourse. I use both, because sometimes appropriation is more accurate. It is the near wholesale exchange of one word for the other as practiced by certain less than nuanced critics that bothers me. I am not comfortable telling Kenneth Branagh that he is appropriating Shakespeare when he thinks he is adapting. Can you tell us your reason for mostly using adaptation in this book?

MPJ: Russell tells me this is a new book, not a third edition of his anthology Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Turning to Shakespeare and World Cinema, I am delighted that you prefer adaptation to appropriation for this book. I deplore the way that appropriation often replaces adaptation in our discourse. I use both, because sometimes appropriation is more accurate. It is the near wholesale exchange of one word for the other as practiced by certain less than nuanced critics that bothers me. I am not comfortable telling Kenneth Branagh that he is appropriating Shakespeare when he thinks he is adapting. Can you tell us your reason for mostly using adaptation in this book?

MTB: I wanted to suggest two things in using that terminology. One, following Colin MacCabe in True to the Spirit that the work of adaptation is creative. When a film is generated from a play, a new text – of value–is fashioned out of an old one, and we are sensitized to how both interrelate. Second, I wanted to try to deploy Fredric Jameson’s understanding of adaptation (explored in the above book, True to the Spirit) that adaptations work as allegories of a struggle for primacy. It is as a two-way struggle, with different points in between, that I sought to articulate in that book how plays and films relate to each other.

MPJ: I had to adjust my expectations of what Shakespeare films can be when I saw Yī jiǎn méi (English title: A Spray of Plum Blossoms), the Chinese film directed by Bu Wancang in 1931, Maqbool, which you mentioned above, and the Argentinean films known as “Las Shakespeariadas” of Matías Piñeiro. You do not write about all these films in your book, but these are the movies that changed the way I think about Shakespeare films. Please talk about the expectations we bring to the viewing of Shakespeare movies.

MTB: Often, I think those expectations gather about fidelity (that is, how far the films cleave to the plot) and language (that is, how far they use or modernize Shakespearean language). I understand that, but I get more excited by the extent to which films conceptualise (find locational and cultural equivalents for Shakespeare’s settings) or simply invoke categories of the “Shakespearean” for interpretive effect. This is connected to recent developments not so much in Shakespearean criticism as adaptation theory. I recommend in this connection Douglas Lanier’s essay on Shakespeare as rhizome in Alexa Alice Joubin and Elizabeth Rivlin’s collection, Shakespeare and the Ethics of Appropriation.

MPJ: I realize that the films covered in your book are of varied quality and many are noteworthy for quite different reasons. Take us on a tour of some of the most interesting.

MTB: I was really taken by Kaliyattam, directed by Jayaraj, a Keralan adaptation of Othello based around the sacred dance form of teyyam, by As Alegres Comadres, directed by Leila Hipólito, a heritage-based Brazilian adaptation of The Merry Wives of Windsor helmed by a woman director, and by Macbeth, directed Bo Landin and Alex Scherpf, an adaptation made in the Arctic Circle in the Smi language and set in the Ice Globe Theatre.

MPJ: I love the Ice Globe idea. I wonder if you staying with the regional approach in ‘Hamlet’ and World Cinema means that you now have a preferred approach to writing about these films compared to the three different approaches in Shakespeare and World Cinema?

MTB: No, I think I am just continuing to try out different models based on the particular content. It’s a good question, because, although there are many approaches to organizing the material, no one approach is fool-proof or perfect. As yet, I haven’t really tried a historical approach or a thematic approach, so that might be next!

MPJ: A question that applies to both World Cinema books, how did you manage to see and learn about so many films that are not in general circulation in the West, or in the case of the southern hemisphere, in the North?

MTB: I do see all the films I talk about, so, yes, the watching experience is crucial. Film festivals make opportunities available; there are increasing viewing options through digital platforms and streaming services; conferences can provide openings for screenings; and directors are almost always agreeable to making their work accessible (indeed, at my own institution, we have screened a number of world cinema adaptations of Shakespeare in what is invariably a mutually enriching experience for students, academics and practitioners alike).

MPJ: I envy your funding! There are others now working on Shakespeare in world cinema. Who should we read?

MTB: Critics I have already mentioned such as Pascale Aebischer (her Screening Early Modern Drama does so much to enrich understanding of auteurs such as Derek Jarman and Alex Cox), Thomas Cartelli, Alexa Alice Joubin (see above), Douglas Lanier (see above), Courtney Lehmann (see above), Katherine Rowe (co-authored with Cartelli, New Wave Shakespeare on Screen addresses films as texts and introduces some vital new critical vocabularies), Jyotsna Singh (see above), Lisa Starks (‘“Remember me”: Psychoanalysis, Cinema, and the Crisis of Modernity’ in Shakespeare Quarterly, brilliantly brings together the rise of psychoanalysis and the emergence of cinema) and Poonam Trivedi (see above and below) are doing great work as are early career scholars such as Thea Buckley and Rosa Maria Garcia Periago, whom I am lucky enough to work with on the “Indian Shakespeares” project at Queen’s. The focus and the landscape are certainly changing. My own work didn’t come out of nowhere, I should add, and I have learned from the example of critics such as Richard Burt, Dennis Kennedy (his collection, Foreign Shakespeare, was really the first work to steer us away from Anglophone Shakespeares) and Kenneth Rothwell (A History of Shakespeare on Screen, 2e, is both impressively magisterial and pithily anecdotal), all of whom have done a great deal to bring world Shakespeares to wider attention.

MPJ: What are the most important books on Shakespeare films you have read?

MTB: I have to name two: they are older, now, of course, but, as books that changed/launched a discipline, I still admire Jack Jorgens, Shakespeare on Film and Anthony Davies, Filming Shakespeare’s Plays. Both are distinguished by really energizing aesthetic engagements with their examples.

MPJ: Are there any books that you refer to frequently?

MTB: I tend to move on to new books with new topics to explore, but right now I find myself going back to Poonam Trivedi and Dennis Batholomeusz’s collection, India’s Shakespeare, because there is so much in it!

MPJ: Such as?

MTB: An attention, for example, to language, translation, performance history, cinema and folk theatre.

MPJ: Do any older books deserve more attention than they have received?

MTB: Yes, Kathy M. Howlett’s book Framing Shakespeare on Film is informed, poetic and distinctive: it impresses in the rigour and invention with which it uses a “framing” theoretical template.

MPJ: Name a Shakespeare book that is just plain fun.

MTB: Not so much fun, but certainly extraordinarily engaging in that it is both critical and personal/autobiographical, is Jonathan Gil Harris’s Masala Shakespeare, which concerns Harris’s own encounter with Indian Shakespeares.

MPJ: I am glad you mentioned Gil. He is such a nice guy and helped me revise a proposal for an SAA seminar on Shakespeare documentaries until it was acceptable for the St. Louis meeting a few years back. Are any non-lit-crit books that you have found particularly enriching in your thinking and writing about Shakespeare and Shakespeare film?

MTB: Gail McConnell’s recent poetry collection, Fothermather, is richly allusive and winningly eloquent. I learn from its relevance, expressions and insights.

MPJ: What are you reading now?

MTB: I am re-reading John D. Smith’s translation of The Mahabharata and reading the memoir of Guardian journalist, Deborah Orr, Motherwell. Particularly with The Mahabharata, I am struck by how consistently and intertextually Indian Shakespeare films meld Shakespeare’s play and the epics.

MPJ: Are there any books you’d like to mention, but I lacked the wit to ask about?

MTB: Peter W. Marx’s Hamlet Handbuch is really a one-stop guide to everything Hamletian!

MPJ: My first encounter with the word Hamletian. My little German is decades old. Can I read Marx’s book?

MTB: Yes, I am sure you could read it, as the book is written in German and English.

MPJ: Are there any important subjects where the books are out of date, and need to be replaced?

MTB: I would love to see Part III of Richard Burt and Lynda E. Boose’s collection, Shakespeare the Movie, which would continue the process of adding new essays to this great work.

MPJ: What needs are there crying out for a book that perhaps you don’t want to write?

MTB: There is a real need for an encyclopedia on Shakespeare and Global Television. It would require a huge team and several editors, but it really would be worth doing.

MPJ: What is the “Shakespeare and Adaptation” series?

MTB: The “Shakespeare and Adaptation” series, recently launched, provides in-depth discussions of a dynamic field and showcases the ways in which, with each act of adaptation, a new Shakespeare is generated. The series aims to address the phenomenon of Shakespeare and adaptation in all of its guises and to explore how Shakespeare continues as a reference-point in a generically diverse body of representations and forms, including fiction, film, drama, theatre, performance and mass media. We’re planning both books and edited collections.

MPJ: I am glad SN can help get the word out. Tell us about the Kenneth Branagh Archive. How did it come about and is Branagh still adding to it?

MTB: Branagh, as you will know, was born and bred in Belfast. We contacted him some years ago to ask if he would be agreeable to his archive being donated to Queen’s, and he was! Since then, the archive has been added to regularly and is used in educational and commemorative programmes. We had an exhibition from the archive as part of the 2016 Shakespeare celebrations.

MPJ: Is the archive accessible to researchers?

MTB: It most certainly is accessible to scholars. See the guide to the archive at: https://www.qub.ac.uk/directorates/InformationServices/TheLibrary/SpecialCollections/FileStore/Filetoupload,677760,en.pdf.

MPJ: Thanks, Mark. I really appreciate you consenting to be my guest in this column.

MTB: Thank you, Mike. This has been a pleasure and an honour. I am in your debt for such finely researched and thought-provoking questions.

Works Cited

Pascale Aebischer, Screening Early Modern Drama: Beyond Shakespeare (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

Victoria Bladen, Sarah Hatchuel and Natalie Victoria Bladen, Shakespeare on Screen: King Lear (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, Film Art, 11e (McGraw-Hill, 2016).

Douglas Bruster, Drama and the Market in the Age of Shakespeare (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

John Burnett, Destiny Obscure: Autobiographies of Childhood, Education and Family From the 1820s to the 1920s (Allen Lane, 1982).

_____, Useful Toil: Autobiographies of Working People from the 1820s to the 1920s (Allen Lane, 1974).

Mark Thornton Burnett, Constructing ‘Monsters’ in Shakespearean Drama and Early Modern Culture (Palgrave, 2002).

_____, Filming Shakespeare in the Global Marketplace (Palgrave, 2012).

_____, ‘Hamlet’ and World Cinema (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

_____, Masters and Servants in English Renaissance Drama and Culture: Authority and Obedience (Palgrave, 1997).

_____, Shakespeare and World Cinema (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Mark Thornton Burnett, Courtney Lehmann, Marguerite Rippy and Ramona Wray, Great Shakespeareans: Welles, Kurosawa, Kozintsev, Zeffirelli (Bloomsbury, 2013).

Mark Thornton Burnett and Adrian Streete, eds., Filming and Performing Renaissance History (London: Palgrave, 2011).

Mark Thornton Burnett, Adrian Streete, and Ramona Wray, eds., The Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and the Arts (Edinburgh University Press, 2011).

Mark Thornton Burnett and Ramona Wray, eds., Screening Shakespeare in the Twenty-First Century (Edinburgh University Press, 2006).

_____, Shakespeare and Ireland: History, Politics, Culture (Macmillan Press Ltd., 1997).

_____, Shakespeare, Film, Fin de Siècle (Macmillan Press Ltd., 2000).

Richard Burt and Lynda E. Boose, eds., Shakespeare the Movie and Shakespeare the Movie II (Routledge, 1997 and 2003).

Maurizio Calbi, Spectral Shakespeare: Media Adaptations in the Twenty-First Century (Palgrave, 2013).

Dympna Callaghan, ed., A Feminist Companion to Shakespeare, 2e (Blackwell, 2016).

Thomas Cartelli, Katherine Rowe, New Wave Shakespeare on Screen (Polity, 2007).

Kate Chedgzoy, Shakespeare’s Queer Children: Sexual Politics and Contemporary Culture (Manchester University Press, 1995).

Henry Chettle, Piers Plainness: Seaven Yeres’ Prentiship (1595).

Jessica Chiba, “Lost and Found in Translation: Hybridity in Kurosawa’s Ran,” Shakespeare Bulletin 36:4, 2019, pp. 599-633.

Janet Clare and Stephen O’Neill, Shakespeare and the Irish Writer (University College Dublin Press, 2010).

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Monster Theory: Reading Culture (University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

Samuel Crowl, Shakespeare and Film: A Norton Guide (W. W. Norton & Company, 2007).

_____, Shakespeare in the Cineplex: The Kenneth Branagh Era (Ohio University Press, 2003).

Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750 (Zone Books, 1998).

Anthony Davies, Filming Shakespeare’s Plays: The Adaptations of Laurence Olivier, Orson Welles, Peter Brook, and Akura Kurosawa (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Thomas Dekker, The Shoemaker’s Holiday (London: 1600).

Andrew Dickson, Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys Around Shakespeare’s Globe (Bodley Head, 2015).

Frances Dolan, Dangerous Familiars: Representations of Domestic Crime in England, 1550-1700 (Cornell University Press, 1994).

Thomas Deloney, Jack of Newbury (London: 1626).

Peter Donaldson, “Hamlet among the Pixelvisionaries: Video Art, Authenticity and ‘Wisdom’ in Almereyda’s Hamlet,” A Concise Companion to Shakespeare on Screen, Diana E. Henderson, ed., (Blackwell, 2006), pp. 225-37.

Margaret W. Ferguson, “Moderation and its Discontents: Recent Work on Renaissance Women,” Feminist Studies, 20:2, 1994, pp. 349-66.

John Ford, ‘Tis Pitty Shee’s a Whore (London: 1633).

Gabriel Egan, The Struggle for Shakespeare’s Text: Twentieth-Century Editorial Theory and Practice (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

David Evett, Discourses of Service in Shakespeare’s England (Palgrave, 2005).

Ewan Fernie, Ramona Wray, Mark Thornton Burnett, and Clare McManus, eds, Reconceiving the Renaissance: A Critical Reader (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Juliet Fleming, Graffiti and the Writing Arts of Early Modern England (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

Stephen Greenblatt, Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare (University of Chicago Press, 1980).

Jonathan Gil Harris, Masala Shakespeare: How a Firangi Writer Became Indian (Aleph Books, 2018).

Sarah Hatchuel and Natalie Vienne-Guerrin, Shakespeare on Screen: Hamlet (Mont-Saint-Aignan Publications des Universités de Rouen et du Havre, 2011).

_____, Shakespeare on Screen: The Henriad (Mont-Saint-Aignan Publications des Universités de Rouen et du Havre, 2008).

_____, Shakespeare on Screen: A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Mont-Saint-Aignan Publications des Universités de Rouen et du Havre, 2004).

_____, Shakespeare on Screen: Othello (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

_____, Shakespeare on Screen: Richard III (Mont-Saint-Aignan Publications des Universités de Rouen et du Havre, 2005).

_____, Shakespeare on Screen: The Tempest and the Late Romances (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

_____, Shakespeare on Screen: The Roman Plays (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Sarah Hatchuel, Natalie Vienne-Guerrin, and Victoria Bladen, Shakespeare on Screen: Macbeth (Publications des Universitiés de Rouen and du Harve, 2014).

Diana E. Henderson, “The Artistic Process: Learning from Campbell Scott’s Hamlet,” A Concise Companion to Shakespeare on Screen, Diane E. Henderson, ed., (Blackwell, 2006), pp. 77-95.

Barbara Hodgdon, The Shakespeare Trade: Performance and Appropriations (University of Philadelphia Press, 1998).

Kathy M. Howlett, Framing Shakespeare on Film: How the Frame Reveals Meaning (Ohio University Press, 2000).

Russell Jackson, ed., Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film, 2e (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

_____, The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Screen (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

Michael P. Jensen, “Comic Book Shakespeare, parts 1-3,” Shakespeare Newsletter, 56:4-57:2, Winter 2006-Fall 2007.

Ben Jonson, The Alchemist. A Comedy (London: 1609).

_____, Volpone or The Foxe (London: 1607).

Jack J. Jorgens, Shakespeare on Film (Indiana University Press, 1977).

Alexa Alice Joubin, Chinese Shakespeares: Two Centuries of Cultural Exchange (Columbia University Press, 2009).

_____, “Global Shakespeares as Methodology,” Shakespeare, 9:3, 2013, pp. 273-90.

Dennis Kennedy, ed., Foreign Shakespeare: Contemporary Performance (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Douglas Lanier, “Shakespearean Rhizomatics: Adaptation, Ethics, Value” Shakespeare and the Ethics of Appropriation, Alexa Alice Joubin and Elizabeth Rivlin, eds. (Palgrave, 2014), pp. 21-40.

Courtney Lehmann, Shakespeare Remains: Theater to Film, Early Modern to Postmodern (Cornell University Press, 2002).

Patrick Lonergan, “’I found it out by the bogs’: Reviewing Shakespeare in Ireland,” Shakespeare 6:3, 2010, pp. 343-9.

_____, “Shakespearean Productions at the Abbey Theatre, 1970-1985,” Donald E. Morse, ed., Irish Theatre in Transition (Palgrave, 2015).

Colin MacCabe, True to the Spirit: Film Adaptation and the Question of Fidelity (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Gail McConnell, Fothermather (Ink Sweat & Tears, 2019).

Emer McHugh, Irish Shakespeares: Gender, Sexuality, and Performance in the Twenty-First Century (Routledge, forthcoming).

Peter W. Marx, Hamlet Handbuch: Stoffe, Aneignungen, Deutungen (J. B. Metzler, 2014).

Sara Mendelson and Patricia Crawford, Women in Early Modern England, 1550–1720 (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Madhavi Menon, Shakesqpeer: A Queer Companion to the Complete Works of Shakespeare (Duke University Press, 2011).

Thomas Middleton and William Rowley, The Changeling (London: 1622).

Andrew Murphy, “Ireland, Ethnicity and the Nation: A Shakespearean Drama,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 16:2, 2016, pp. 206-217.

Michael Neill, Putting History to the Question: Power, Politics, and Society in English Renaissance Drama (Columbia University Press, 2000).

Lena Cowen Orlin, Private Matters and Public Culture in Post-Reformation England (Cornell University Press, 1994).

Deborah Orr, Motherwell: A Girlhood (Weidenfeld & Nicholson 2020).

Stephen Prince, The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa – Revised and Expanded Edition (Princeton University Press, 1999).

Mary Prior, “Women and the urban economy: Oxford 1500–1800,” Women in English society 1500–1800, Mary Prior ed., (Taylor and Francis, Ltd., 1985), pp. 53-88.

Kenneth Rothwell, A History of Shakespeare on Screen, 2e (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

David Schalkwyk, Shakespeare, Love and Service (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Katherine Schiel, ed., Shakespeare and Stratford, (Berghahn, 2019).

Richard Schoch, “The Birth of Shakespeare’s Birthplace,” Theatre Survey 53:2, 2012, pp. 181-201.

Samuel Schoenbaum, Shakespeare’s Lives, New Edition (Clarendon Press, 1991).

James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (Yale University Press, 1990).

Alan Sinfield, Faultlines: Cultural Materialism and the Politics of Dissident Reading (Oxford University Press, 1992).

Alan Sinfield and Jonathan Dollimore, eds., Political Shakespeare: New essays in cultural materialism (Manchester University Press, 1985).

Jyotsna G. Singh, Shakespeare and Postcolonial Theory (Bloomsbury, 2019).

John D. Smith, trans., The Mahabharata (Penguin, 2009).

Lisa Starks, “’Remember me’: Psychoanalysis, Cinema, and the Crisis of Modernity, Shakespeare Quarterly 53:2, Summer 2002, pp. 181-200.

Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic (Scribner, 1971).

Ayanna Thompson, “What Is a ‘Weyward’ Macbeth?’, Weyward Macbeth: Intersections of Race and Performance, Ayanna Thompson and Scott L. Newstock, eds. (Palgrave, 2010), pp. 3-10.

Rosemarie Garland Thompson, Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (Columbia University Press, 1997).

Poonam Trivedi and Dennis Batholomeusz, eds., India’s Shakespeare: Translation, Interpretation and Performance (University of Delaware Press, 2005).

Poonam Trivedi and Paromita Chavravarti, eds., Shakespeare and Indian Cinemas: “Local Habitations” (Routledge, 2019).

John Webster, The Duchess of Malfi (London: 1623).

S. White, Avant-Garde Hamlet: Text, Stage, Screen (Fairleigh Dickinson Press, 2015).

Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema (Duke University Press, 2000).

Filmography

As Alegres Comadres, Leila Hipólito, dir. (Ananã Produções, 2003).

Freaks, Tod Browning, dir. (Universal, 1932).

Gamlet, Grigori Kozintsev, dir. (Lenfilm, 1964).

Hamlet, Campbell Scott and Eric Simonson, dirs. (Spare Room Productions, 2000).

Hamlet, Michael Almereyda, dir. (Miramax Films, 2000).

Hamlet, Stephen Cavanagh, dir. (Derry Film Initiative, 2005).

Hermia and Helena, Matías Piñeiro, dir. (Interior X II I, 2016)

Kaliyattam, Jayaraj, dir. (Jayalakshmi Films, 1997).

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Adrian Noble, dir. (Edenwood, 1996).

La Princesse de France, Matías Piñeiro, dir. (Interior X II I, 2014).

Macbeth, Bo Landin and Alex Scherpf, dirs., (Scandinature Films, 2004).

Maqbool, Vishal Bhardwaj, dir. (Kaleidoscope Entertainment Pvt. Ltd., 2003).

Rosalinda, Matías Piñeiro, dir. (Jeonju Digital Project, 2010).

Viola, Matías Piñeiro, dir. (Interior X II I, 2012).

Yī jiǎn méi (English title: A Spray of Plum Blossoms), Bu Wancang, dir. (Lianhua Film Company, 1931).